Carl R. Weinberg

12 October 2021Riding with a California Creationist

by Carl R. Weinberg

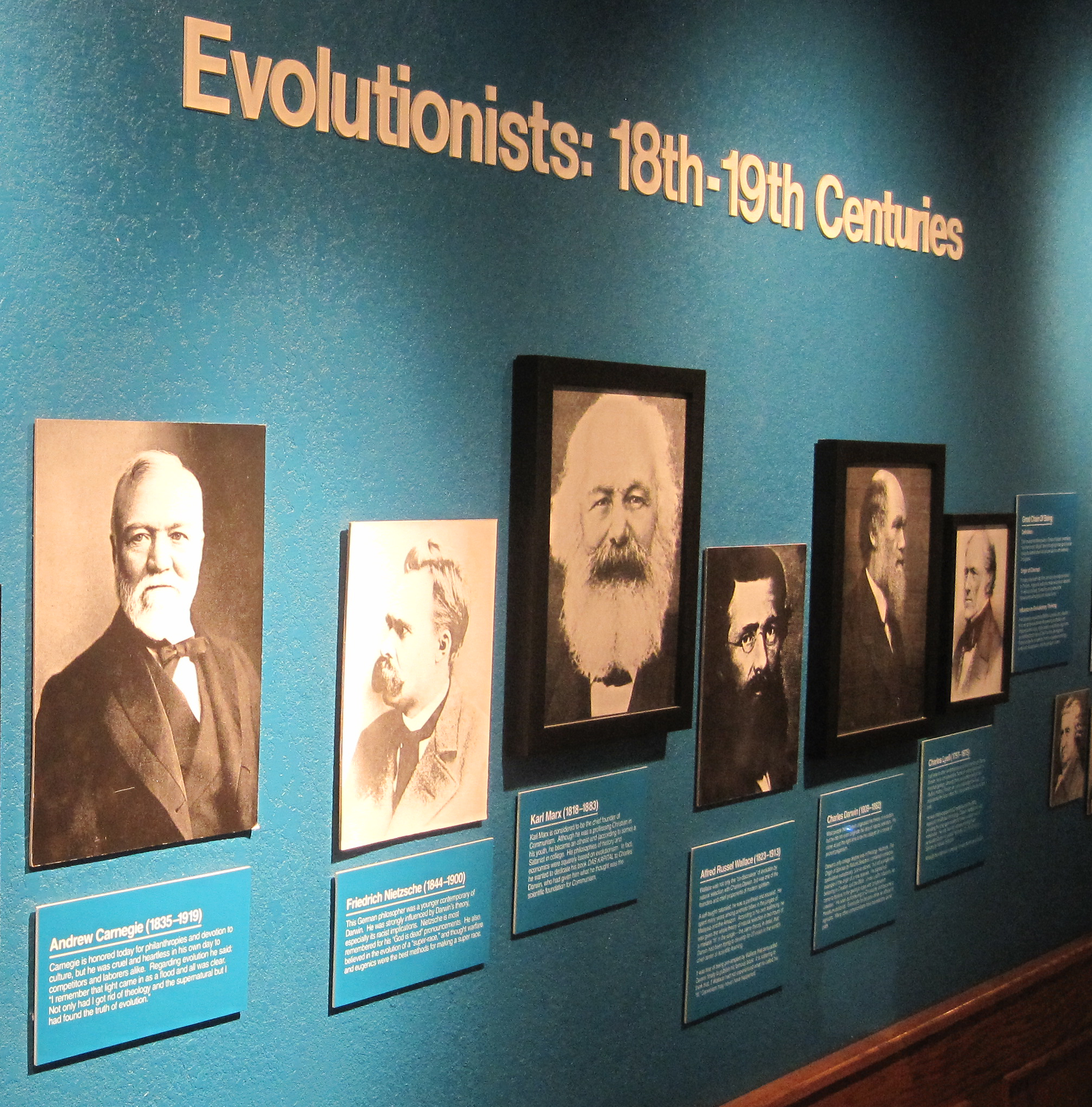

Originally conceived as a Prologue to Red Dynamite and written in 2013, this essay profiles Tom Cantor, the owner of the Creation and Earth History museum in Santee, California, and my transnational experience interviewing him from the back of an armored car.

It is the afternoon of November 16, 2012, and we have just stopped at the Mexican border. We’re about to cross into Tecate, Baja California, home of the eponymous beer and a slew of foreign-owned factories—maquiladoras—that run on cheap Mexican labor. For the last hour, we have driven through the hilly scrubland southeast of San Diego. From the back seat, I have been interviewing Tom Cantor, owner of Scantibodies Laboratory, Inc. whose plant in Tecate manufactures medical testing products. Through his Light and Life Foundation, Cantor is also the owner of the suburban San Diego-based Creation and Earth History Museum, formerly the property of the Institute of Creation Research (ICR). As we get out of the car to walk through the U.S. Customs and Border Protection station, Cantor is telling me how he became a creationist.

The emperor has no clothes

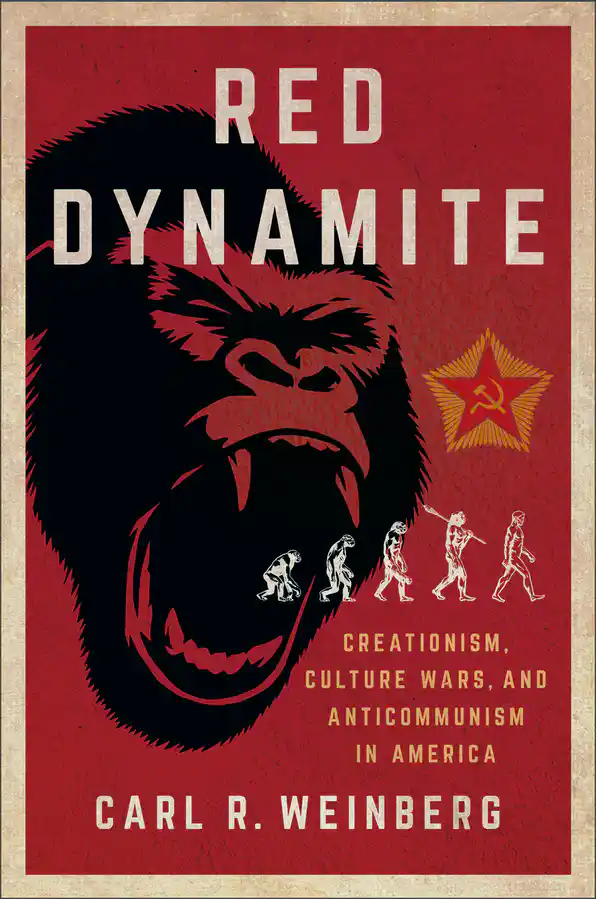

It was 1970, and nineteen-year-old Tom Cantor was taking a class with the famous physical chemistry professor at UC San Diego, the Nobel Prize–nominee Stanley Miller. In 1952, Miller and Harold Urey had conducted a ground-breaking experiment seeking to explain the origin of life on earth. They were testing the hypothesis of abiogenesis put forward by Soviet biochemist A. I. Oparin and British geneticist and Marxist J. B. S. Haldane. Oparin and Haldane began with a key principle of the Marxist philosophy of dialectical materialism: the transformation of quantity into quality. They hypothesized that the inorganic conditions of early earth gave rise to organic molecules—a qualitative leap to life from non-life. By applying electrodes to a mix of gases in a “sparking chamber,” Miller and Urey succeeded in producing some amino acids, a hint that life could arise without God.

Chemist Stanley Miller and the set-up of his famous 1952 experiment.

Chemist Stanley Miller and the set-up of his famous 1952 experiment.

As a well-read undergraduate student in Miller’s class, Cantor took the opportunity to visit his esteemed professor’s office hours and ask him some tough questions about the limits of his results. To Cantor’s amazement, Miller did not have a convincing answer. He ended the conversation by saying, “I do not know. I am still searching for how life began.” Walking out of Miller’s office, Cantor concluded that if his illustrious professor could not explain the origin of life without God, then God must have been involved.

As I listen to Cantor tell his story, I am impressed that he had the chutzpah and knowledge to question his professor. I am also thinking about what we share in common: our Jewish heritage and a Jewish sense of humor. When I turned on my digital recorder and asked Cantor if I could interview him, he chuckled and said, “I’m Terri Gross, and this is Fresh Air.” But I am also struck by the logical inference Cantor drew from that conversation with his Nobel Prize-winning professor. Science, it seems, was supposed to provide the truth with absolute certainty. If even eminent scientists were still looking for answers, then that truth must reside beyond science. For me, in contrast, it was that very process of “searching” that made science an endless adventure. When I was a kid, it meant walking for an hour with my brother and our friends to collect insects in Miller Meadow Forest Preserve, near my hometown of Oak Park, Illinois. Not knowing—and the curiosity it generated—made science exciting. It led me to say, at that tender age, when I wondered what I would do when I grew up, that “I’m going to be a scientist!” In any event, based on the research I had already done for this book, I had a hunch that Cantor’s creationist conclusions did not flow simply or even primarily from the intellectual limitations of Miller’s experiment.

Crossing the border

Now in Mexican territory, we hop into an armored black SUV with tinted windows, driven by a Scantibodies employee. Cantor tells me that the car can withstand the impact of two grenades. Kidnappings of wealthy business owners have been rife, and so Cantor is not taking any chances. He and his wife started Scantibodies in their garage with $120 dollars in 1973. Company revenues in 2011 were more than $60 million, with 775 employees and offices in Japan, China, and Ethiopia. As we approach the plant, Cantor points to the adjoining land, which was once part of extensive farming operation. There are still orange and olive trees growing there, along with grapes, which are harvested for wine.

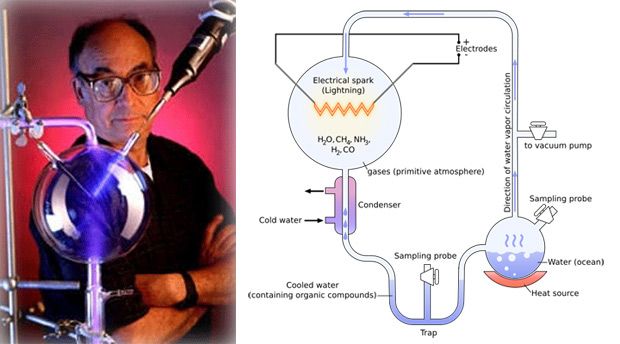

Display in Institute of Creation Research museum in Santee, California, c. 2000.

Display in Institute of Creation Research museum in Santee, California, c. 2000.

Creationists, I had learned, are fond of horticultural analogies. Before Cantor bought the ICR creation museum in 2008, one display depicted the evil “fruits” growing on the evolution tree. Cantor hasn’t seen the exhibit—ICR took it down some time before selling the museum—but he recalls that the museum currently points to Nazism, abortion, and racism as consequences of evolutionary thinking. He quotes from the subtitle of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species—the “preservation of favoured races”—and comments that such language is “absolute dynamite today.” I ask him about communism as a “fruit” of evolution. Cantor is not sure about that—“We stick with racism and Hitler.” The claim that Hitler’s embrace of evolutionary thinking makes Darwin somehow responsible for the Holocaust has become common currency in creationist circles.1 I resist the temptation to engage him on this point, though it is hard for me to distance myself from the subject. My mother was a refugee from Nazi Germany, and her grandparents perished in the death camps. My father was the child of Russian Jewish immigrants escaping the post–World War I pogroms in the former Russian empire. He wrote his master’s thesis on the German Communist Party. And I had learned from my own study of history and politics that ideas—isolated from social, political, and economic forces, embodied in human beings—were not responsible for much of anything.

A “communist” enterprise

As we roll into the plant parking lot, Cantor is telling me about how different his company is from the other maquiladoras, where annual labor turnover is high. At Scantibodies, it’s only 2 percent. Labor is still far cheaper than in the U.S.—the starting wage here for an unskilled worker is $1.25 an hour. But his workers stay because Cantor has created a “community.” The plant contains not only production facilities, but a low-cost daycare, school, medical clinic (which even offers cancer treatment), and a cafeteria where food is made from fresh ingredients daily. “People love it when they get here,” Cantor says. Playing off my communism question, Cantor jokingly adds, “We have a commune. We’re communist.” Unions, of course, are nowhere to be found in the Tecate industrial zone. “I was just reading about Hostess Twinkies and Dingdongs,” Cantor says, in reference to the just-concluded Hostess strike that ended with the company declaring bankruptcy. “That was the strike that killed . . . “Eighteen and a half thousand employees, imagine that.”

I have to bite my tongue for this part of the conversation. I have spent a fair share of time walking picket lines in solidarity with workers on strike. I am the son and grandson of union members. As a graduate student at Yale, I helped organize a union movement of graduate employees. The very fact that I am interviewing Cantor for a book about creationism and anticommunism stems from my pro-labor activism. I first seriously encountered writing about evolutionary science in the Militant bookstore, run by the Socialist Workers Party in Washington, D.C. They carried revolutionary Pathfinder books but also copies of Stephen Jay Gould’s Ever Since Darwin. I was fascinated by Gould’s explanation of why cicadas emerged after intervals of years that were prime numbers. When I hear Cantor mention the Hostess strike, I reflect on the fact that whenever working people organize to defend their interests, their employers hold over them the threat of closing shop and moving to cheaper sources of labor. That is exactly why Scantibodies has a plant in Mexico. The fact that Hostess made good on that threat is not an argument against unions—it’s an argument for international working-class solidarity. But I am not in Tecate to argue labor politics with Tom Cantor.

Tom Cantor at his Scantibodies plant in Tecate, Baja California, 2012.

Tom Cantor at his Scantibodies plant in Tecate, Baja California, 2012.

The Tecate Scantibodies plant is not only unusual for its “communist” tendencies, but also in that it doubles as a satellite creation museum. Walking into the lobby, we are greeted by a gigantic polished rock embedded with orthoceras and ammonite fossils. Walls are adorned with framed Bible passages. As I learn later on the tour, the factory contains a large worship sanctuary, where Cantor shares his personal spiritual journey with his employees. That journey, I would contend, is more central to his creationism than his reasoned assessment of Stanley Miller’s science, and it a features a story of family and personal turbulence.

Becoming a Christian

Cantor’s parents were divorced when he was one. Young Tom Cantor was a “troublesome” kid. After he was arrested for shoplifting, his parents sent him to a Los Angeles military school, from which he was soon expelled. In his teenaged years, he always felt a “tremendous sense of unrest.” That led his parents to once again ship him off for his education. After graduating from a Swiss boarding school, he returned to the U.S. in 1967, but was dismayed by a “frightening” America, full of the “acid revolution . . . anarchy . . . hatred and rebellion.” To make matters worse, he felt guilty, “unclean and defiled” by his adventures in sexual “immorality” while in Switzerland.

As Cantor tells his plant employees and has recounted in an online video, a published booklet and a DVD, the turning point came at Miami University where he spent his early college years. Escaping from Los Angeles, he hoped that the “wheat fields of Ohio” would have a “calming” effect on his turbulent passions. But it was his future wife Cheryl who made the difference. She was a devout Christian and young-earth creationist who had read Henry Morris and John Whitcomb, Jr.’s Genesis Flood. He was a skeptical Jew who had never seriously read the Bible. Before long, the two had married, Cantor’s family disowned him for marrying a non-Jew, he began to study the New Testament in earnest, and the young couple moved to San Diego, where they aimed to finish their college education. There, Cantor visited a Baptist church and at the age of nineteen was born again. All the feelings of guilt and uncleanliness immediately left him.2

And since that day in 1970, Cantor has been a devoted Christian. As a converted Jew, he has adopted a special mission, through Israel Restoration Ministries, to convert other Jews to Christianity. That commitment has colored his view of President Obama, whom he sees as an “enemy of the Jewish people” and a secret Muslim. On the “birther” issue, Cantor thinks that “Trump is right”—Obama is not a U.S. citizen. Cantor also became a young-earth creationist and supporter of ICR. His campus group at UCSD sponsored a debate between ICR’s Duane Gish and a physics professor. Henry Morris spoke at Cantor’s church. And many years later, when ICR leaders told him that they were moving to Dallas, he offered to buy their museum.

“We don’t like militancy”

As we drive back to San Diego, no longer in the grenade-proof car, the desert sun is setting and the late autumn air is getting chilly. I ask Cantor about Henry Morris’s contention that evolutionary ideas started with the Devil. Evolution does have an atheistic tendency, says Cantor. But he’s reluctant to say that it came from the Devil himself. Satan is “very real,” he says. But if creationists get “emotional” about evolution, he explains, they say things they regret and then they have to go back and “clean up the words.” That’s why Cantor is also skeptical about the idea that evolution laid the basis for communism. If he tried to make that argument, he added, “I would immediately think of all the critics and how I couldn’t defend it.” When it comes to evolution, Cantor says, he prefers a low-key approach. He sees himself as an “open door,” providing a way for people to find Christ and creation. “But we don’t like militancy.”3

Cantor’s comment makes me smile. The parade of figures who populate Red Dynamite had no such compunctions about taking a strong stand. I think of creationist geologist George McCready Price to whom I am indebted for my title. In a chapter of The Predicament of Evolution (1925) entitled “Red Dynamite,” Price explained how the threat of a revolutionary movement to overthrow capitalism was intertwined with evolutionary science. As he wrote, “Marxian Socialism and the radical criticism of the Bible . . . are now proceeding hand in hand with the doctrine of organic evolution to break down all those ideas of morality, all those concepts of the sacredness of marriage and of private property, upon which Occidental civilization has been built during the past thousand years.” In Price’s view, evolution was explosively dangerous because it threatened to upend prevailing moral standards and a whole range of social and political hierarchies. He devoted his life to stopping that explosion.4 As it turns out, what most alarmed Price and like-minded creationists was not biological, but social evolution. This conclusion jives with Tom Cantor’s comments on the “hatred,” “anarchy, and “rebellion” he witnessed in the 1960s. It also speaks to his overwhelming concern with sexual immorality.

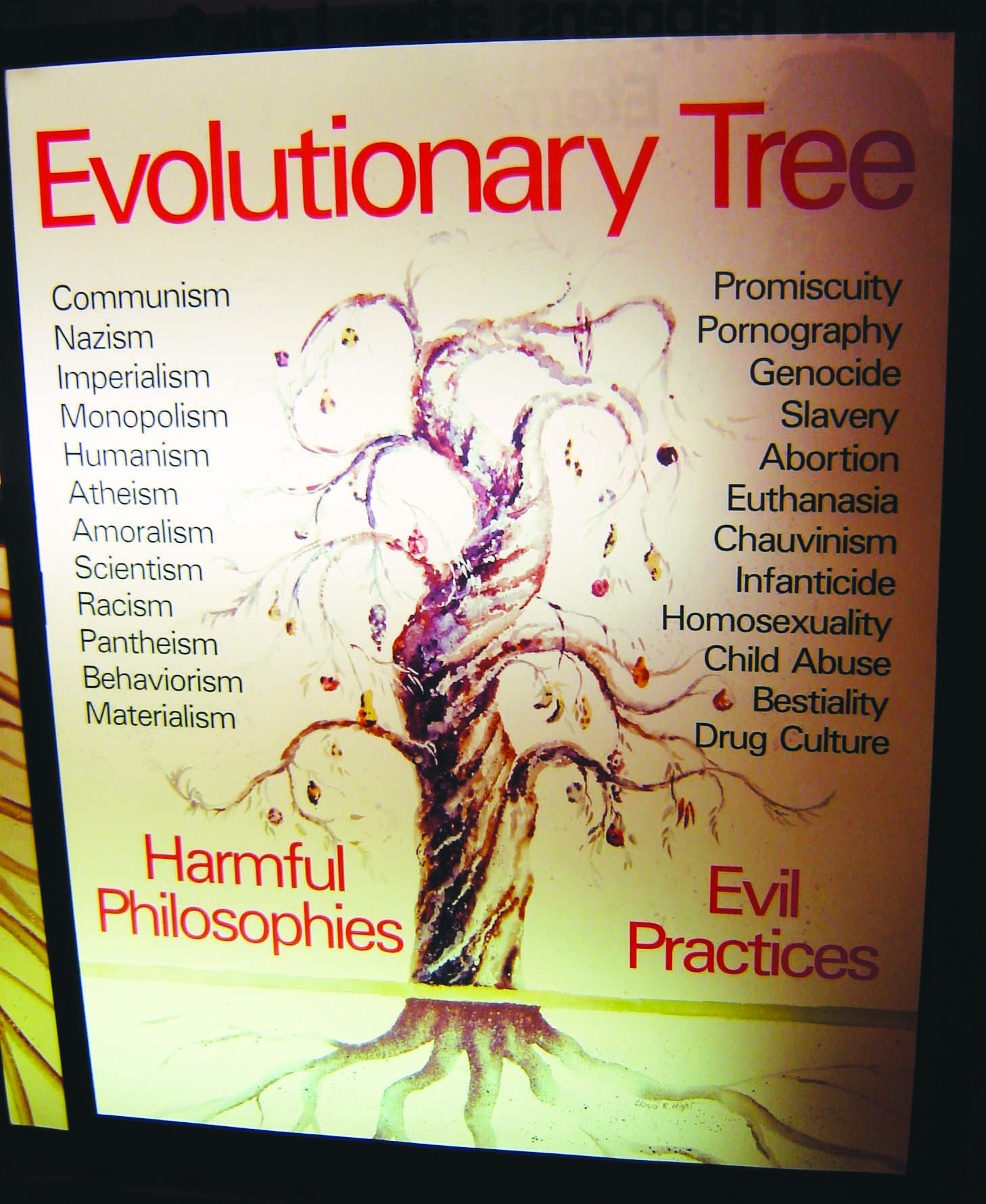

Panel from Creation and Earth History Museum, Santee, CA, 2012

Panel from Creation and Earth History Museum, Santee, CA, 2012

Left-wing social Darwinism

But I am sympathetic to Cantor’s skeptical reaction to the claim that evolution and communism are diabolically connected. Most of us learn that the social and political implications of evolutionary science are exemplified by a conservative ideology called “social Darwinism,” the opposite of communism. Its best-known poster-boys—capitalists Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller—appear prominently in the Hall of Scholars exhibit at Cantor’s museum. The display text links Carnegie’s “cruel and heartless” treatment of his steel workers to his embrace of evolution and rejection of “the supernatural.” Rockefeller’s “ruthless” treatment of his competitors in the oil industry is attributed to his theistic evolutionism. But hovering above all of the other “scholars” in the museum exhibit is none other than Karl Marx. Visitors learn that, “Although he was a professing Christian in his youth,” Marx “became an atheist and (according to some) a Satanist in college.” Marx was not a Satanist. But as I document in my book’s first chapter, Marx, Engels, Lenin, Trotsky and all manner of socialists and communists in the US during the twentieth century were fervid evolutionists. (As was Soviet biochemist Oparin, whose ideas prompted the Miller-Urey experiment.) Left-wing “social Darwinism” was real, and creationists noticed.

And thus, they gave me the opportunity to write an entire book about their responses. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed exploring this vast, untapped area of investigation.

Notes

-

The best-known proponent of this view is Richard Weikart. See From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). For a critique of his claims, see Sander Gliboff’s review. ↩

-

In 2020, eight years after I visited Cantor, he published a new version of his autobiography, in which he revealed a secret that had been haunting him for decades. Before he married his wife-to-be Cheryl, she informed him that she had been raped and was pregnant with the rapist’s child. According to Cantor, this meant that Cheryl was no longer “pure, wholesome, and innocent.” She could no longer rescue Cantor from his own “defilement.” It was this revelation more than anything else, it turned out, that led Cantor to accept Jesus. The Cantors gave up Cheryl’s newborn daughter for adoption. And they kept this secret for nearly fifty years until their son, upon doing a 23andme search, discovered he had a half-sister. See Tom Cantor, Changed (Tom Cantor, 2020), 28–56, 73–75. ↩

-

Interview with Tom Cantor, Santee, California and Tecate, Baja California, Mexico, November 16, 2012. ↩

-

Ronald Numbers, The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006; expanded edition), 88–119; Carl R. Weinberg, ““Ye shall know them by their fruits”: Evolution, Eschatology, and the Anticommunist Politics of George McCready Price,” Church History 83 (September 2014): 684–722. ↩