Carl R. Weinberg

17 November 2021The Man Behind the Metaphor: The Subversive Legacy of Alfred Nobel

by Carl R. Weinberg

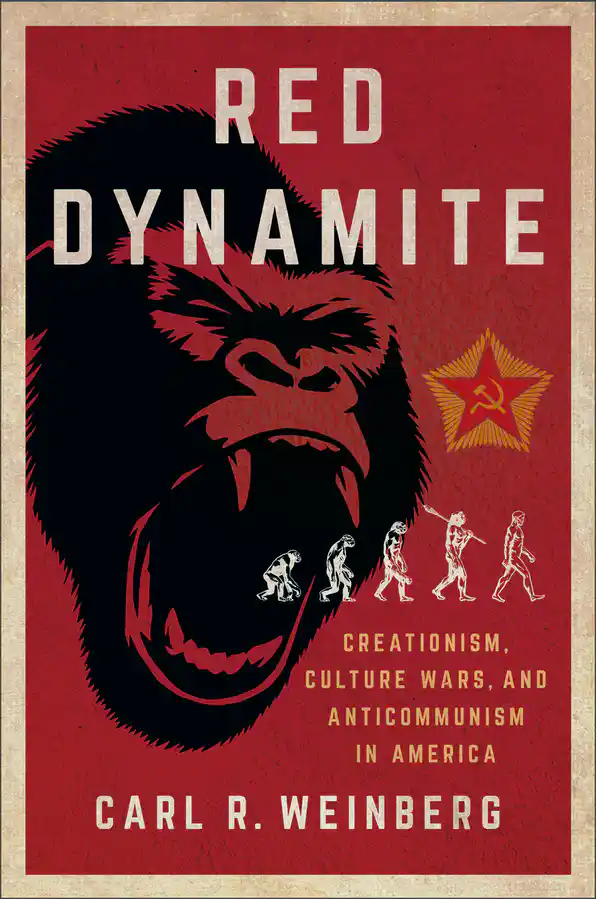

When I was finishing up my book on the Red Dynamite metaphor, I decided that it would be wise to learn something about actual dynamite and its Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel. Thanks to a business trip my wife and I took to Stockholm, I was able to walk the streets of Nobel’s birthplace, visit the Nobel Foundation Museum, and read a little-known play by Nobel in the Royal Library. What I found, pardon the pun, blew me away. I hope you enjoy this piece, which I originally intended as part of the introduction to the book.

Dynamite candy souvenir from the Nobel Foundation Museum, Stockholm, Sweden.

Dynamite candy souvenir from the Nobel Foundation Museum, Stockholm, Sweden.

In 1883, Swedish playwright and poet August Strindberg (1849–1912) penned a poetic homage to Alfred Nobel (1833–96), the Swedish-born inventor of dynamite. Strindberg used a publishing metaphor to favorably compare dynamite, “a huge popular edition, constantly renewed in a hundred thousand copies,” with gunpowder, “a small edition published for the nobles and the princely houses.”1 Nobel, in Strindberg’s estimation, had provided ordinary working people with the means— inexpensive, easily available, and safe to handle,—to fight oppression and tyranny. Only two years earlier, a group of Russian populists organized into the People’s Will had used Nobel’s new invention to assassinate Tsar Alexander II on the streets of St. Petersburg. In the coming decades, dynamite was the weapon of choice among a wide range of Russian revolutionaries.2 Strindberg was no stranger to violent controversy. Declaring himself in 1880 a “socialist, a nihilist, a republican, anything that is opposed to the reactionaries,” he stood trial for blasphemy in 1884 after publishing a collection of short stories on marriage that challenged existing gender and sexual norms and portrayed the Lutheran church as a tool of the rich to fleece the Swedish masses.3

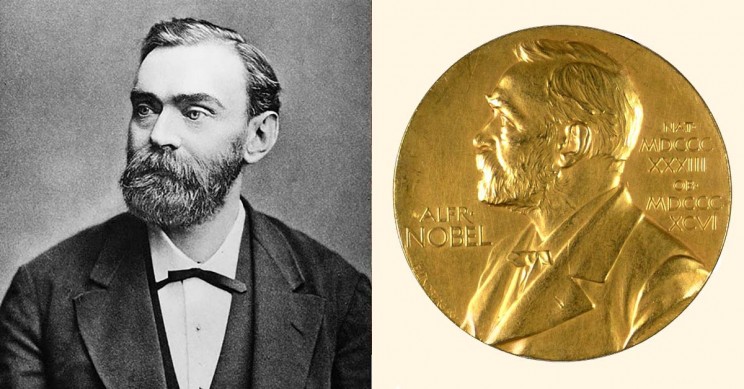

Alfred Nobel (1833-1896), inventor of dynamite.

Alfred Nobel (1833-1896), inventor of dynamite.

Strindberg’s poem points to an intriguing connection between real dynamite and the metaphorical variety as expressed by creationist geologist George McCready Price in 1925. When he described the explosively immoral convergence of evolutionary ideas and Marxism as “Red Dynamite” in 1925, he surely knew that Alfred Nobel had invented that explosive and that it was employed by opponents of the established political, economic, and social order. He was also well aware of the associations commonly made between socialism, evolution, atheism, and immorality. As an amateur geologist, Price also might have known that the key ingredient that Nobel added to nitroglycerine to make the compound stable was diatomaceous earth, a sedimentary deposit made up of fossilized diatoms, a single-celled aquatic algae that evolutionary geologists date as far back as the Jurassic period.4 What Price may not have known, however, is just how intimately tied together were Alfred Nobel, evolutionary ideas, alleged blasphemy, and working-class revolution in Russia. The historical context of actual dynamite, that is, provides an illuminating entryway into the history of the Red Dynamite metaphor.

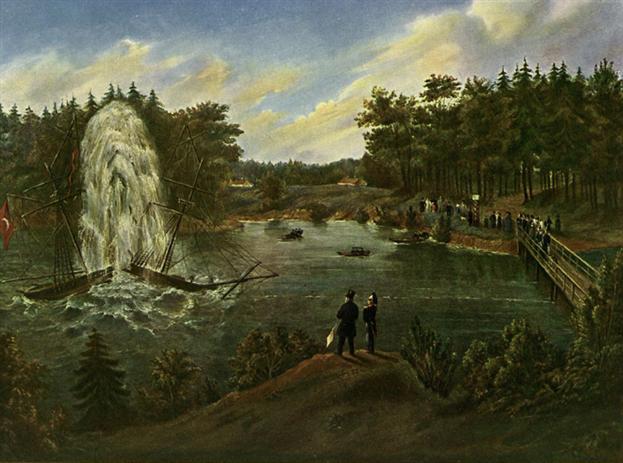

The education of Alfred

Alfred Nobel spent much of his childhood in St. Petersburg, Russia, where his engineer father Immanuel Nobel did a brisk business selling naval mines to the Czarist regime of Nicholas I during the Crimean War.5 The young Nobel was tutored by leading figures in science and became fluent in six languages. When the family returned to Sweden, Alfred traveled to the U.S., Britain, and Germany, where he received further training in chemistry.

Alfred Nobel’s father Immanuel demonstrates his underwater mines to Czar Nicholas I. Water color painting by Immanuel Nobel.

Alfred Nobel’s father Immanuel demonstrates his underwater mines to Czar Nicholas I. Water color painting by Immanuel Nobel.

Not surprisingly for a cosmopolitan scientist, inventor, and businessman in the mid-nineteenth century, Nobel became an avowed evolutionist and, like Strindberg, a critic of established religion. One indication of the former is Nobel’s personal library, part of which is today on display at the Nobel Foundation in Stockholm. His books included Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) and an approvingly annotated copy of Haeckel’s History of Creation (1876), a popular defense of Darwin’s ideas. Nobel also kept a philosophical notebook, which contains his jottings on a wide range of thinkers, from Greek materialist Democritus to the Prussian geographer and philosopher of science Alexander von Humboldt, who profoundly influenced Darwin. On the question of why people believe in God, Nobel wrote, “Aristotle attributes it to fear, Voltaire to the desire of the more clever to deceive the stupid.” An indication that Nobel tended to side with Voltaire comes in his comments on the scientific method, which he understood, in the most general terms, as a study of similarities and differences. “The only exception to this rule is religious doctrine,” Nobel wrote, “but even this rests on the similar gullibility of most people.”6

Nobel drops a bomb

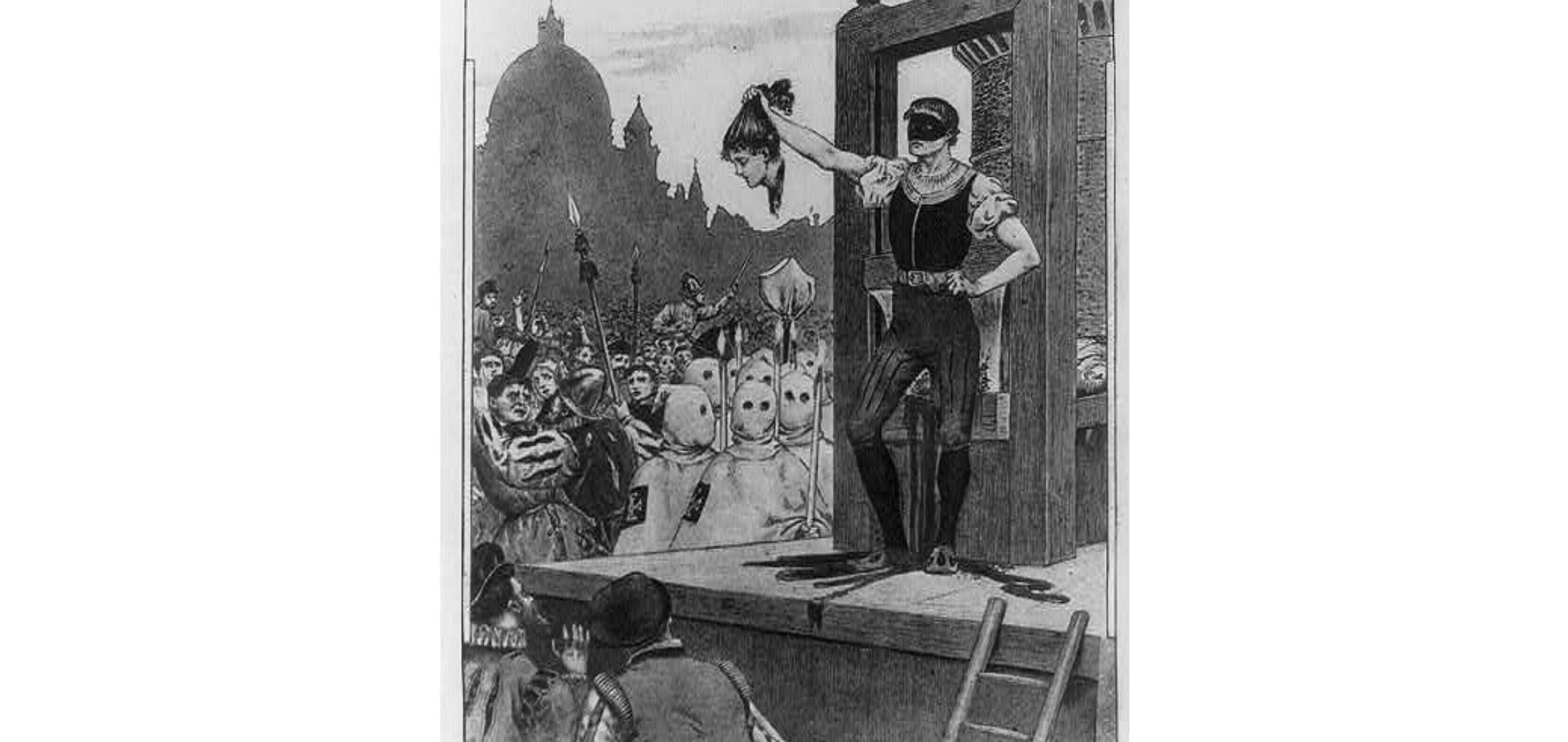

The most politically explosive of Nobel’s anti-religious writings—a play entitled Nemesis (1896)—almost failed to see the light of day, since his family succeeded in destroying all but three copies as soon as they were published in the weeks after his death. The play was Nobel’s attempt to retell the story of Beatrice Cenci, a young Italian woman executed on September 11, 1599 for the murder of her father, Count Francesco Cenci. As retold by a series of writers, most notably Percy Bysshe Shelley in The Cenci (1819), Count Cenci was an abusive and violent man who raped his own daughter. In revenge, Beatrice conspired successfully with her mother, brother, and two of the family’s servants to kill the family patriarch. Beatrice Cenci maintained her innocence to the end, but was beheaded for her crime by the Neapolitan authorities, under order from the Pope.7

An 1895 engraving of the 1599 execution of Beatrice Cenci.

An 1895 engraving of the 1599 execution of Beatrice Cenci.

Despite a longstanding oral tradition about this sordid affair and a string of written accounts, the subject matter—incest and parricide—was considered so controversial that even Shelley’s play was not publicly performed until 1922.8 A delay of similar length followed the publication of Nobel’s work—it was performed for the first and only time in Stockholm in 2005 at, appropriately enough, the August Strindberg Intima Theater.9 Among the liberties that Nobel took with the story were his decision to allow Beatrice and her co-conspirators to live. Contrary to the final execution scene in Shelley’s version, Beatrice gets away with murder. And in the play’s final lines, when servant and hired killer Marzio implores his accomplice Olympio to pray to God for forgiveness, Olympio replies, “Right away, as soon as I have counted up my loot.”10

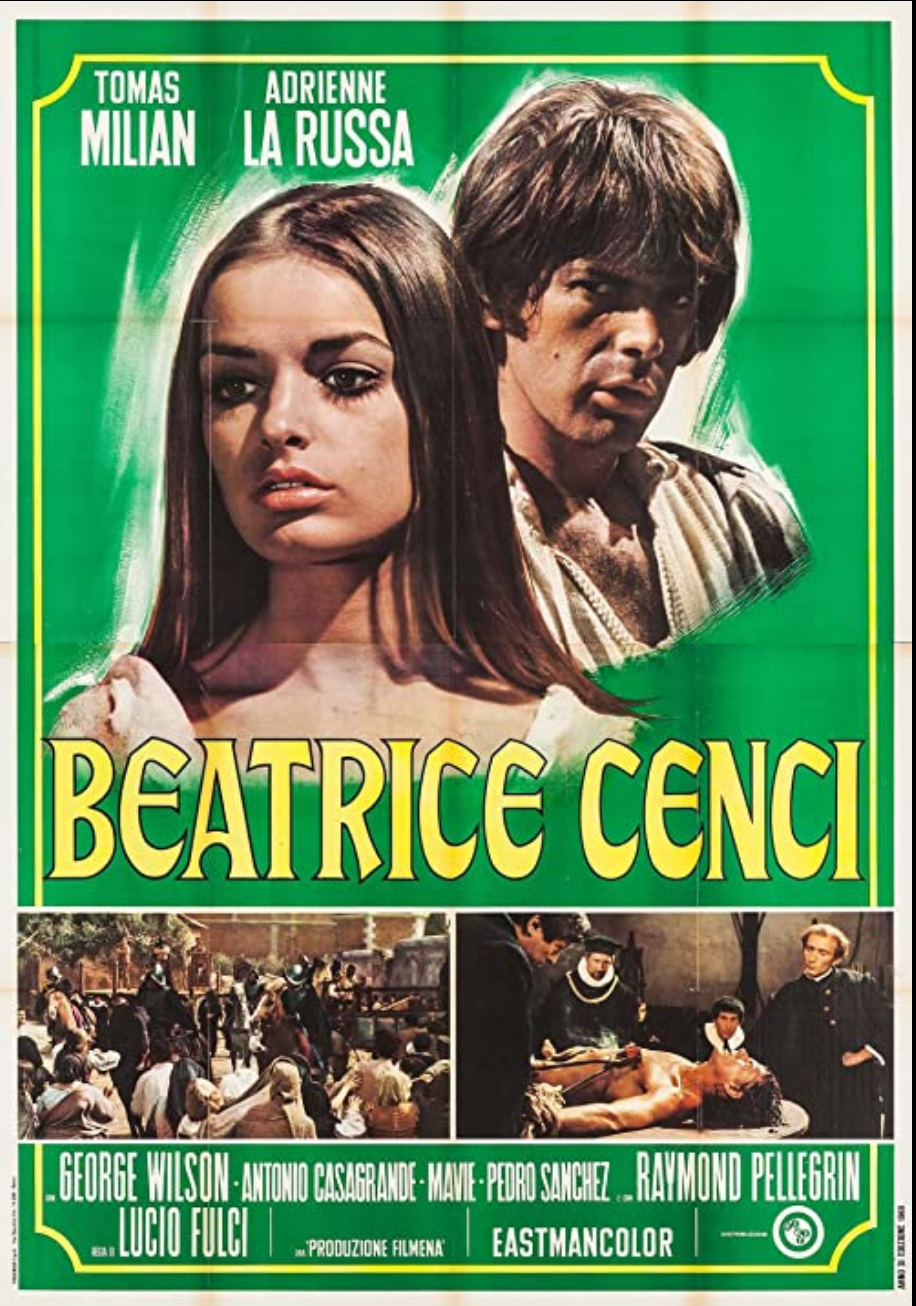

Poster for the Italian film version of the Beatrice Cenci story, 1969.

Poster for the Italian film version of the Beatrice Cenci story, 1969.

Speaking through Satan

As if this twist to the story were not sufficiently irreverent, Nobel added two dream sequences in which Beatrice meets Mother Mary and then Satan, the latter of which is clearly speaking for the author. Beatrice comes across as a wide-eyed innocent in the spirit of Voltaire’s Candide, who through her adventures eventually becomes wise in the ways of the world. In the first dream, Beatrice relays a series of anti-religious comments spoken by her free-thinking brother Guido, to which the Mother Mary responds with indignation. Guido claims that the belief in a divine savior was terribly exploited by the Christian clergy and served as a pretext for “the most atrocious crimes.” To the contrary, Mother Mary explains, it was only the “purest sentiment of human love that gave birth to the instruments of torture and the practice of burning heretics at the stake during the Inquisition.” Indeed, she adds, the torturers were too gentle, given the immense power of the Satanically-induced heresies. But weren’t the Inquisitors steeped in the darkness of fanaticism? asks Beatrice. Didn’t they need enlightenment? No, says the Mother Mary, salvation lies in a return to “perfect ignorance.”11

In Nobel’s hands, Satan offers Beatrice a refreshing contrast to this caricature of blind religious faith. Satan, it seems, is a kind of natural theologist, perhaps even a theistic evolutionist. As he explains to our heroine, he does not bow down to God (whom he and his fellow denizens of the spirit world call “Cosmos”), but he does admire the natural wonders of his creation—from the wonders of a seed growing into a plant, the mechanics of nutrition, the accuracy of the human eye, the powers of memory, or the sensitivity of our nerves. In the eyes of Nobel’s Satan—sounding very much like Baruch Spinoza—God is identical with nature, with the universe. “Primitive matter,” says Satan, “was not created, for it was there for all eternity. The fact that it has been ordered and grouped together in ways that surprise and charm us, that in living form it is born and grows, loves and reproduces, experiences joy and suffers, thinks and acts—is not all of this enough to render the material world worthy of our adoration?“ In response, Beatrice must admire Satan’s eloquence. Madonna, she tells him, is “incontestably more prosaic,” which then leads Satan to offer his opinion on the alleged divinity of Jesus. Mary’s son, he argues, was too noble and modest to claim he was God. Priests invented that idea, Satan explains, “to extract money from the gullible masses.”12

“The Admonishment of Beatrice Cenci,” 1853, by Charles Robert Leslie (1794-1859). The count is at right.

“The Admonishment of Beatrice Cenci,” 1853, by Charles Robert Leslie (1794-1859). The count is at right.

The Evil Count Agrees

Nobel purveys his materialistic, evolutionary vision not only through Satan but also through the otherwise detestable Count Cenci. In a soliloquy during Act I, the Count reinforces Satan’s conception of nature as God and mirrors his critique of organized Christianity. To Cenci, the Christian conception of God’s “almighty Justice” is the “silliest of fables.” Hell is an invention that enables the clergy to fleece “all of humanity.” Based on the example of the early modern Catholic Church, morality itself is nothing but a “mask” to “fool the peasants.” Moreover, argues Cenci, nature itself reflects nothing of the alleged Christian virtues: “There is no pity, no reward for virtuous behavior, no punishment for crime. All creatures prey or are preyed upon, all torment or are tormented, and God’s reward, like that of the state, goes to the strongest.”13 It was Tennyson’s “Nature, red in tooth and claw,” with some Hobbes and possibly Nietzsche thrown in for good measure.14 Thus, Nobel’s play not only deals with rape, incest, and murder but also conveys the author’s pro-evolutionary and anti-religious views through the work’s most conventionally evil characters. It is hardly a shock that his family sought to destroy the book.

Nobel in Russia

When Nemesis was staged in Stockholm in 2005, the Guardian newspaper attributed even more subversive qualities to the dynamite inventor: “Nobel’s raunchy anti-capitalist play gets world premiere.” Although the play does take aim at the complicity of religious authorities in the exploitation and oppression of workers and peasants, “anti-capitalist” goes too far. For all of his contradictions, the capitalist Nobel was wedded to the free enterprise system. But it is fair to say that the giant Nobel oil companies in the Caucasus region of Russia at the turn of the twentieth century, run by Alfred’s brothers and nephews, did play a significant role in laying the foundations for the Bolshevik Revolution.

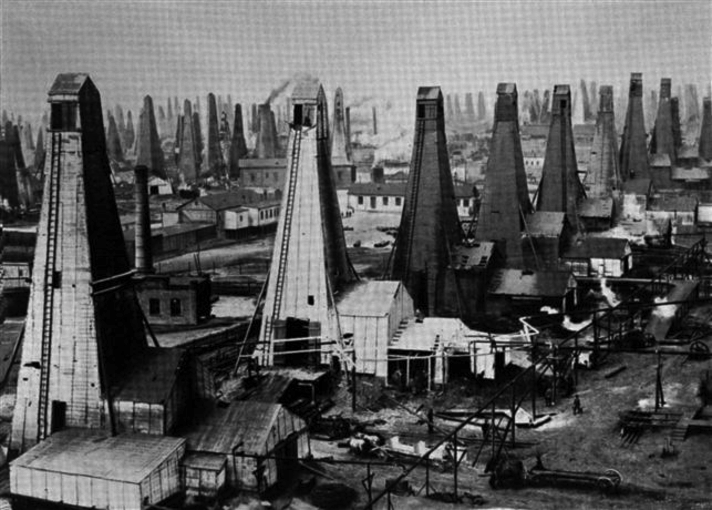

Nobel oil derricks in the Balachany oil field, near Baku, Azerbaijan

Nobel oil derricks in the Balachany oil field, near Baku, Azerbaijan

When Alfred Nobel returned to Sweden with his father, his older brothers, Robert and Ludvig, remained in Russia and by the 1870s had become major players in the Caspian Sea oil industry, centered at Baku in Russian Azerbaijan. Their flagship was the Petroleum Production Company Nobel Brothers, Limited, better known as Branobel, a shortened version of the name in Russian. Though Alfred did not have a hand in day-to-day operations, his considerable investment in Nobel oil companies generated 12 percent of the money that would fund the Nobel prizes. His explosive invention also proved useful. Branobel used four hundred tons of dynamite to blast the way for an oil pipeline from Baku to Batum. The Nobel brothers were innovative in other ways: they were the first to successfully launch an oil tanker and the first to employ a full-time petroleum geologist. The scale of Nobel oil operations was immense. A network of wells, refineries, machine factories, railroads, pipelines, and oil tankers employed some fifty thousand workers at their height in 1916. Annual profits that year were more than seventy-five million rubles. And the Nobel enterprise produced one-third of Russia’s oil.15

Capitalism Its Own Gravedigger?

By setting up this scale of operations and bringing together thousands of working people from across the Russian Empire, the Nobel brothers unwittingly helped to create a modern working class in Czarist Russia. About half of their workers—designated “Christians” in Nobel company records–were ethnic Russians and Armenians; the other half—designated “Muslim”– comprised Azeri workers from northern and southern Azerbaijan (Iran), Iranian Persians, Lazgis from Dagestan, and Kazan Tatars from the Volga region. The former tended to work in the more highly paid positions, in the factories and repair shops, whereas the Muslim workers extracted the oil, and lived in the worst housing conditions, near the source of the black gold.

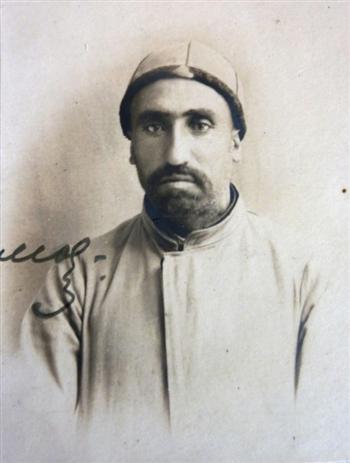

Branobel worker Meshadi Khalil Ibrahim, 25-year-old, from Khalkhala, Persia.

Branobel worker Meshadi Khalil Ibrahim, 25-year-old, from Khalkhala, Persia.

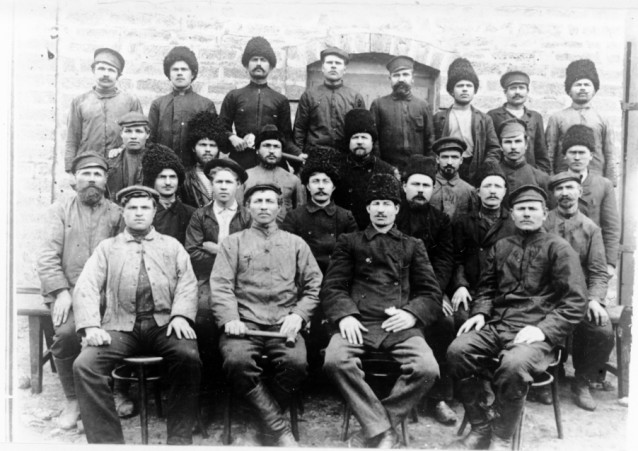

Compared to workers in other parts of industrializing Russia, oil workers were paid relatively well. This was due in part to the need to assure an uninterrupted supply of the black gold to the empire as a whole. But it was also due to the growing strength of organized labor. By the early twentieth century, there were two union federations competing for support among Baku’s oil workers, one a craft union, active among the Russians and Armenians, dominated by the Menshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party and the other, a budding industrial union that aimed to bring together both skilled and unskilled workers, dominated by organizers loyal to the Bolshevik faction of the party.16

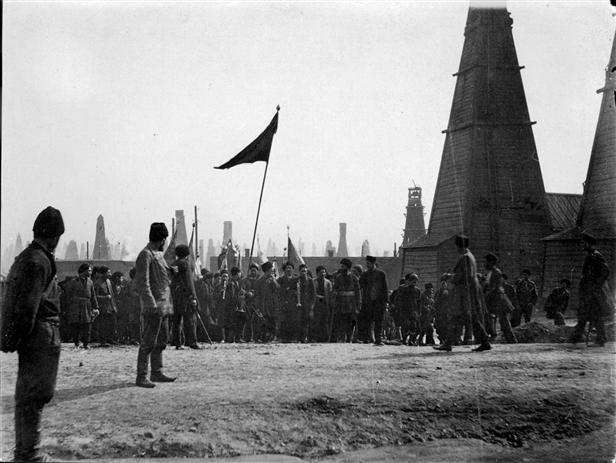

Branobel workers on strike in Baku, 1903.

Branobel workers on strike in Baku, 1903.

Enter Koba

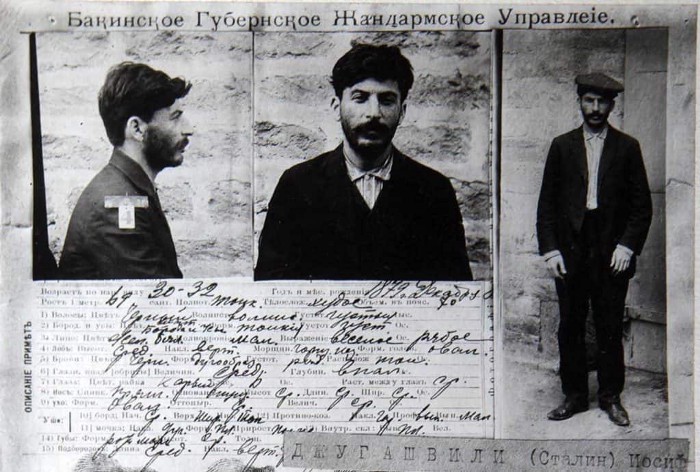

Among those Bolshevik organizers in the Caucasus oil fields was a young Georgian by the name of Joseph Vissarionovich Djugashvili (1879–1953). He had escaped to there from Siberia where he had been exiled after the authorities in Batum, a giant Black Sea oil port, arrested him for subversive socialist activities. When he first arrived in Batum from Tiflis, the Georgian capital, where he had attended theological seminary, he was operating under the alias of Koba. He would soon become world-famous as Stalin.17 While Koba sat in a Batum jail, the RSDLP held its momentous congress in which the party split into Menshevik and Bolshevik wings. When Koba arrived in Baku in 1907, he was firmly allied with the Bolsheviks, who aimed to wrest control of the local SD party from the Mensheviks. He also arrived at a time that has gone down in Russian revolutionary history as “The Reaction,” a period of intensified repression following the failed 1905 revolution. In this context, the Bolsheviks pursued a mix of tactics, mainly working through the established legal union and party organizations, but also continuing to function as an “underground” organization.

Koba under arrest in 1911.

Koba under arrest in 1911.

Expropriating the Expropriators

In this capacity, the Bolsheviks did not shrink from making use of Alfred Nobel’s new invention. The Russian Social Democrats (both Bolsheviks and Mensheviks) had been highly critical of the anarchist advocacy of revolutionary terrorism, arguing that it pointed away from mobilizing the power of the masses of workers and peasants. In 1906, however, the Bolshevik newspaper urged armed party groups to carry out guerrilla actions “with the minimal `destruction of the personal safety’ of peaceful citizens and with the maximum destruction of the personal safety of spies, active members of the Black Hundreds, high-ranking officers of the police, the military, the navy and so on . . .”18 To some extent this willingness to use terror tactics flowed from an assessment by the party leadership that the fires of the 1905 revolution were still burning and so acts of armed resistance by small groups of workers were justified. It was also grounded in the Bolsheviks’ need for money. Then a critic of the Bolsheviks, Leon Trotsky recorded more than a thousand terrorist acts in the Caucuses between 1905 and 1908. They included assassinations of local officials as well as bank robberies of state funds, which the Bolsheviks called “expropriations.” One of the more spectacular expropriations took place in a main square in Tiflis in June 1907. Koba helped to plan the action, though he apparently did not help carry it out. The attackers threw bombs into stage coaches hired by the Tiflis State Bank and they escaped with 250,000 rubles, leaving dozens of casualties.19

Main square in Tiflis, Georgia where 1907 expropriation took place.

Main square in Tiflis, Georgia where 1907 expropriation took place.

Dynamiter-in-Chief

The mastermind behind Bolshevik expropriations was not Koba, but Leonid Krasin (1870–1926), a Siberian-born engineer who joined the Social Democratic movement in the 1890s and became a trusted confidante of Lenin and a member of the Bolshevik Central Committee. From 1900 to 1904, Krasin was based in Baku, where he was hired to build a giant power station providing electricity to oil refineries. His workforce came from all over Europe, leading Krasin to comment that Baku was a “real Babel.” Working as an undercover Bolshevik, Krasin managed to organize “Nina,” the code name for a major clandestine printing press, housed in the Muslim quarter of Baku, which churned out a variety of revolutionary publications, including the Communist Manifesto and Lenin’s Iskra (The Spark) newspaper. Back in Petrograd, Krasin used his technical and scientific knowledge to head up the Petrograd Military Technical Group, which purchased and produced dynamite and other weapons used in the 1905 revolution and then in innumerable expropriations and assassinations during the period of The Reaction. If there was anyone who put Alfred Nobel’s ideas into Bolshevik revolutionary action, it was Leonid Krasin. He would later serve as People’s Commissar of Foreign Trade in the early years of the Bolshevik Revolution.20

House-museum of underground printing-office Nina where newspaper Iskra (Spark) was published in 1901–1905 under the direction of Leonid Krasin.

House-museum of underground printing-office Nina where newspaper Iskra (Spark) was published in 1901–1905 under the direction of Leonid Krasin.

The Oil Wars

The Nobel brothers were not only contending with restive workers and a growing revolutionary movement—the Bolsheviks would expropriate the entire Nobel operation when they took power—but they were competing with the other oil giants: Rockefeller’s Standard Oil and BNITO, owned by the Paris Rothschilds family. BNITO was dominant in Batum, on the Black Sea. Nobel ruled the Baku oilfields—Robert Nobel was known as the “Oil King of Baku” and the “Russian Rockefeller.” And Standard Oil prevailed in European markets, constantly lowering prices to drive their competitors out of business, a tactic that had worked wonders in the United States. They also spread false rumors of the low quality of Russian oil to hurt the Nobels. No tactic was too low in the high-stakes game of the international oil market—including bribery and sabotage. As Nobel’s Count Cenci says, “God’s reward . . . goes to the strongest.” By any means necessary, the Rockefellers, the “Russian Rockefellers,” or the Rothschilds would rule the world.21

Workers of the Rothschilds’ Bibiheybat oil fields. Baku. Photo: Azerbaijan National Photo and Film Archiv

Workers of the Rothschilds’ Bibiheybat oil fields. Baku. Photo: Azerbaijan National Photo and Film Archiv

More than a Metaphor

Evolution, communism, power, deception, morality, sex, violence—all of these themes were present in the century-long political tradition that creationist geologist George McCready Price christened in 1925 with the “Red Dynamite” metaphor. Amazingly enough, they are also embedded in the story of literal dynamite and its enigmatic inventor, Alfred Nobel.

Notes

-

John Eric Bellquist, Strindberg as a Modern Poet: A Critical and Comparative Study (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1896), 14; Raymond Williams, “The politics of the avant-garde,” in Visions and Blueprints: Avant-garde Culture and Radical Politics in Early Twentieth-Century Europe, Edward Timms and Peter Collier eds., (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1988), 1. ↩

-

Derek Offord, The Russian Revolutionary Movement in the 1880s (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 28; Anna Geifman, Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia, 1894–1917 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993). ↩

-

Anna Westerhahl Stenport and Eszter Szalczer, “Strindberg and Radicalism—Strindberg and the Avant-garde: A Hundred-Year Legacy,” Scandinavian Studies 84 (Fall 2012): 240–41; August Strindberg, Getting Married (New York: Viking Press, 1972), 11–48, 61; Michael Meyer, Strindberg (New York: Random House, 1985), 130–42. ↩

-

F. E. Round, R. M. Crawford, D. G. Mann, The Diatoms: Biology and Morphology of the Genera (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 123–24. ↩

-

Kenne Fant, Alfred Nobel: A Biography, trans. Marianne Ruuth (New York: Arcade Publishing, 1993; orig. pub. 1991), 26–31. ↩

-

Tore Frangsmyr, “Alfred Nobel—Life and Philosophy,” Nobelprize.org (Nobel Media AB 2014), December 8, 1998; Ake Erlandsson, “[Alfred Nobel and His Interest in Literature] https://www.nobelprize.org/alfred-nobel/alfred-nobel-and-his-interest-in-literature/),” Nobelprize.org (Nobel Media AB 2014), July 23, 1997; Author’s notes on visit to Nobel Foundation Museum, Stockholm, Sweden, July 1, 2016. ↩

-

Fant, Alfred Nobel: A Biography 16. ↩

-

Kenneth N. Cameron and Horst Frenz, “The Stage History of Shelley’s The Cenci,” PMLA 60 (December 1945): 1085; Charles Nicholl, “Screaming in the Castle: The Case of Beatrice Cenci,” London Review of Books 20 (July 2, 1998): 23–27. ↩

-

“Nobel’s raunchy anti-capitalist play gets world premiere,” The Guardian, September 8, 2005. ↩

-

Alfred Nobel, Némésis, trans. Régis Boyer (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2008; orig. pub. 1896),152. The text in French is: “Tout de suite, dès que j’aurai compté mon or.” Many thanks to Professor Bengt Sandin of Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, for comparison with the original Swedish text. Remarkably, Nemesis has not been translated into English. ↩

-

Alfred Nobel,Némésis, 74–75. ↩

-

Ibid., 83–85. ↩

-

Ibid., 48. ↩

-

On Tennyson’s famous formulation from his 1850 poem, “Memoriam,” and its relation to the evolutionary thought of the day, see Kenneth M. Weiss, “`Nature, Red in Tooth and Claw,’ So What?,” Evolutionary Anthropology 19 (2010): 41–45. ↩

-

Kenne Fant, Alfred Nobel, 224. ↩

-

Ronald Grigor Suny, “A Journeyman for the Revolution: Stalin and The Labour Movement in Baku, June 1907–May 1908,” Soviet Studies 23 (January 1972): 375–77. ↩

-

Isaac Deutscher, Stalin: A Political Biography (New York: Vintage Books, 1960; orig. pub. 1949), 2, 45–48. ↩

-

Geifman, Thou Shalt Kill, 91–92. ↩

-

Ibid., 87–88, 113. ↩

-

Michael Glenny, “Leonid Krasin: The Years Before 1917,” Soviet Studies 22 (October 1970): 192–221; Timothy Edward O’Connor, The Engineer of Revolution: L. B. Krasin and the Bolsheviks, 1870–1926 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1992), 40, 69–74. ↩

-

Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 58–62. ↩