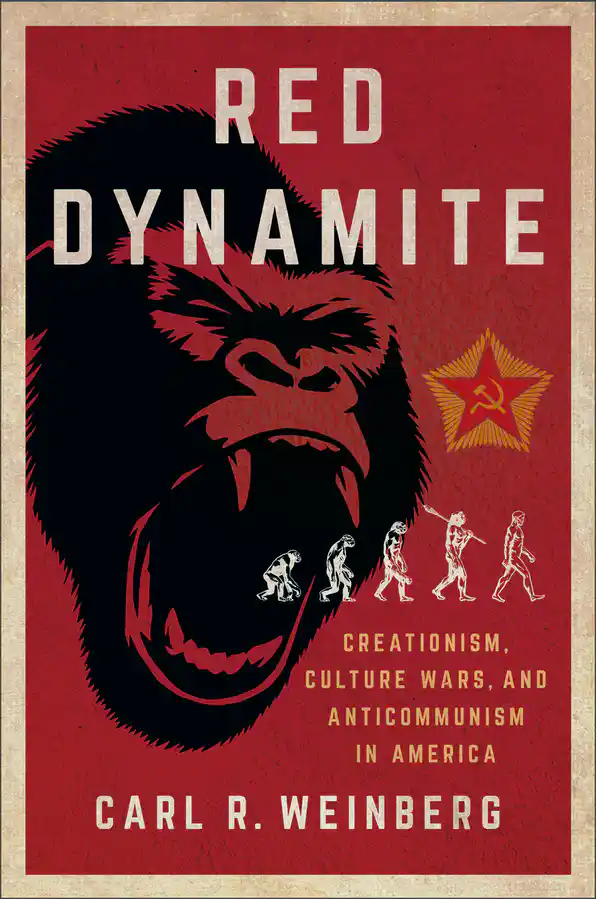

Carl R. Weinberg

25 January 2022The Jungle Beat: Evolution, Communism, Race, and David Noebel’s Campaign against Rock ‘n’ Roll

by Carl R. Weinberg

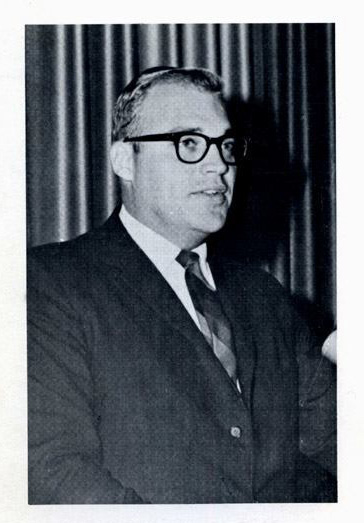

Reverend David A. Noebel (1936– ) appears in chapters 6 and 9 of Red Dynamite as a leading anticommunist who spent decades shining a bright light on the connections, both real and imagined, between communism and evolutionary science. Working for Billy James Hargis’s Christian Crusade in the early 1960s, Noebel founded the Anti-Communist Youth University (now Summit Ministries) in Manitou Springs, Colorado, to train a new generation of Red-hunters.

Here I write about Noebel’s infamous campaigns against rock ‘n’ roll in the 1960s. Claiming that the music was part of a communist plot to instigate youth rebellion, Noebel employed openly racist arguments about the “savage” roots of rock ‘n’ roll. Even though Noebel did not openly invoke Darwin as the culprit, by linking popular music, animal behavior, sex, race, and immorality, Noebel helped to lay the foundation for subsequent culture wars over the teaching of evolutionary science to the nation’s young people.

Housed in an historic hotel with a stunning view of Pikes Peak, David Noebel’s Anti-Communist Youth University in Manitou Springs, Colorado is now known as Summit Ministries.

Housed in an historic hotel with a stunning view of Pikes Peak, David Noebel’s Anti-Communist Youth University in Manitou Springs, Colorado is now known as Summit Ministries.

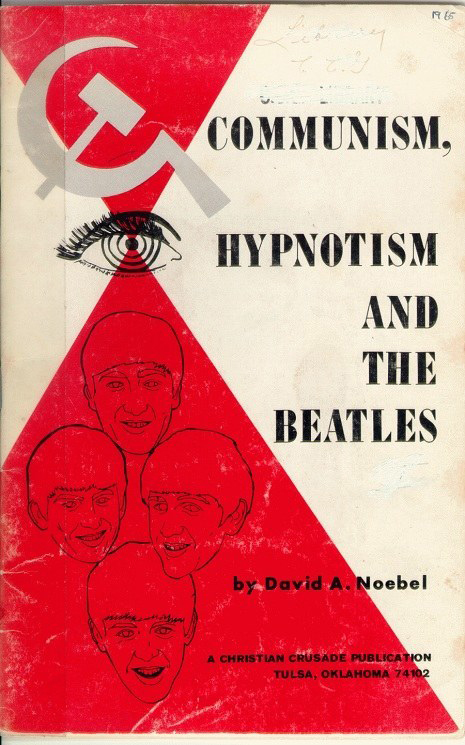

Nerve Jamming American Youth

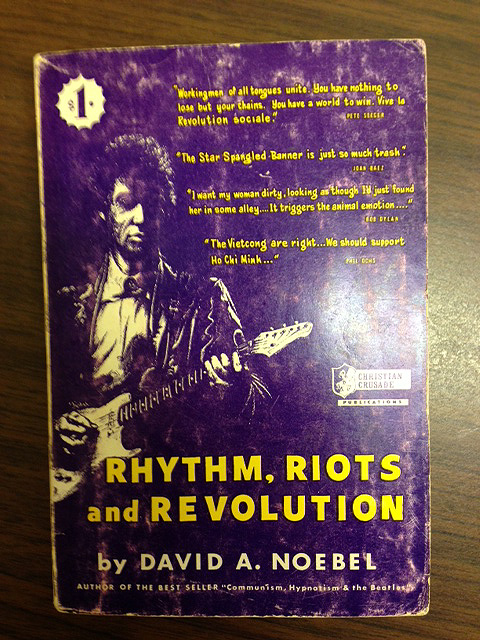

In a series of works published by the Christian Crusade—Communism, Hypnotism and the Beatles (1965), Rhythm, Riots and Revolution (1966), Suffer Little Children (1967), and The Marxist Minstrels (1974)—Reverend David Noebel advanced a startling thesis: folk and rock ‘n’ roll music constituted a weapon wielded by the international communist conspiracy to “nerve-jam” American youth and turn them into pliable accomplices of revolt against the American capitalist establishment.

Reverend David A. Noebel in the mid-1960s

As bizarre as such claims sound today, Noebel’s charges harmonized well with the widely-publicized work of journalist Edward Hunter who argued that the Soviets and Chinese had perfected “brainwashing” techniques building on the early experiments in psychological “conditioning” pioneered by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov in his experiments with dogs. Communist agents as well as communist-sympathizing musicians, according to Nobel, were using such techniques—such as writing music that accorded with the human heartbeat—to create a “frenzied, hypnotic state.” “The frightening —even terrifying—aspect of this mentally conditioned process,” Noebel warned, “is the fact that these young people, in this highly excited, hypnotic state, can be told to do practically anything—and they will.” Imagine, then, if the “enemies of the Republic” used the Beatles and other to “send them forth into the streets to riot and revolt.”1

Rock music–loving young people ridiculed Noebel’s claims. His critics took heart from a mocking portrait of Noebel’s crusade in Newsweek magazine entitled, “Beware, the Red Beatles.” Still, Noebel did present convincing evidence that the Communist Party and fellow-travelers had consciously exerted significant influence on American folk music, extending to “mainstream” icons such as the Fireside Book of Folk Songs.2 His claims about rock ‘n’ roll were more indirect. They focused not on Communist Party cultural workers, but rather on the alleged atheistic and communistic leanings of figures such as Beatles’ John Lennon and of crossover singers like Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. Regardless of whether or not Noebel convinced his readers, he displayed considerable research skill, drawing upon U.S. government documents, press accounts, scientific journal articles, music history, and Communist literature to support his claims. Rhythm, Riots and Revolution contained dozens of footnotes and twenty-six appendices.3

Newsweek (November 15, 1965) pokes fun at Noebel’s claims about the Beatles and communism.

Newsweek (November 15, 1965) pokes fun at Noebel’s claims about the Beatles and communism.

The Animal Emotion

In all of this work, evolution is not far below the surface. It underlies Noebel’s references to the work of Ivan Pavlov whose essay on the brain had graced the Russian centennial volume on Darwin in 1909. In 1913, Pavlov explained just how important Darwin was to his own work: “In all justice, Charles Darwin must be given the major credit for stimulating and inspiring the modern comparative study of the higher [psychic] manifestations of animal life.”4 Noebel did not expose Pavlov as a Darwinian, but his extensive description of experiments by Pavlov and his colleagues inevitably drew attention to human as animal. Just as the backlash against Alfred C. Kinsey’s reports and male and female sexuality focused on the sexologist’s view of human beings as “animals,” Noebel played up the connections between young people’s visceral, emotional “animal” reaction to music and their sexual desires. The menacing portrait of Bob Dylan on the Rhythm, Riots cover was accompanied by the following Dylan quotation: “I want my women dirty, looking as though I’d just found her in some alley . . . It triggers the animal emotion . . . “ Animalism also had political consequences, as the advertisement for Rhythm, Riots in Christian Crusade made evident: “The book proves that the riots in Berkeley . . . the insurrection in Watts . . . were in part inspired by this jungle beat Communist[-]planned music . . .”5

A sinister-looking Bob Dylan links sex and the “animal emotion.”

Rhythmic Chants of Primitive Peoples

As the reference to the 1965 Watts urban rebellion suggests, Noebel’s concept of music-inspired sexual animalism had a clear racial, and racist, dimension.6 Noebel notes that the Communists were calling for breaking down the barrier between classical European music and popular American music. This meant, Nobel concludes, citing American Communist cultural spokesman Sidney Finkelstein, a focus on rock ‘n’ roll music’s African roots.7 “The goal,” warned Noebel, “is to inundate the American people with African music! Disparage the importance of good classical music and standard musical form!” To bolster his claims about the downward and dangerous musical direction of Africanized popular music, Noebel quoted plentifully from Pulitzer Prize–winning American composer and then-director of the Eastman School of Music, Howard Hanson, about the evil effects of jazz, or as he called it, “the violent boogie-woogie.” In a 1944 article in the American Journal of Psychiatry Hanson compared the “mass hysteria” of the “rhythmic chants of primitive peoples” with the “similar mass hysteria of the modern jam session.” By subjecting young people to such music, averred Hanson, America was becoming “a nation of neurotics.” In a similar vein, Noebel quoted as an authority on the consequences of rock ‘n’ roll, Dimitri Tiomkin, a well-known conductor and Oscar-winning Hollywood film composer. In 1965, Tiomkin pointed to the phenomenon of “so-called concerts” of rock ‘n’ roll turning into riots as evidence that “we seem to be reverting to savagery.”8

An excerpt from Howard Hanson’s article in the mis-titled, “Some Objective Studies of Rhythm in Music,” American Journal of Psychiatry (November 1944)

Reversion to Savagery

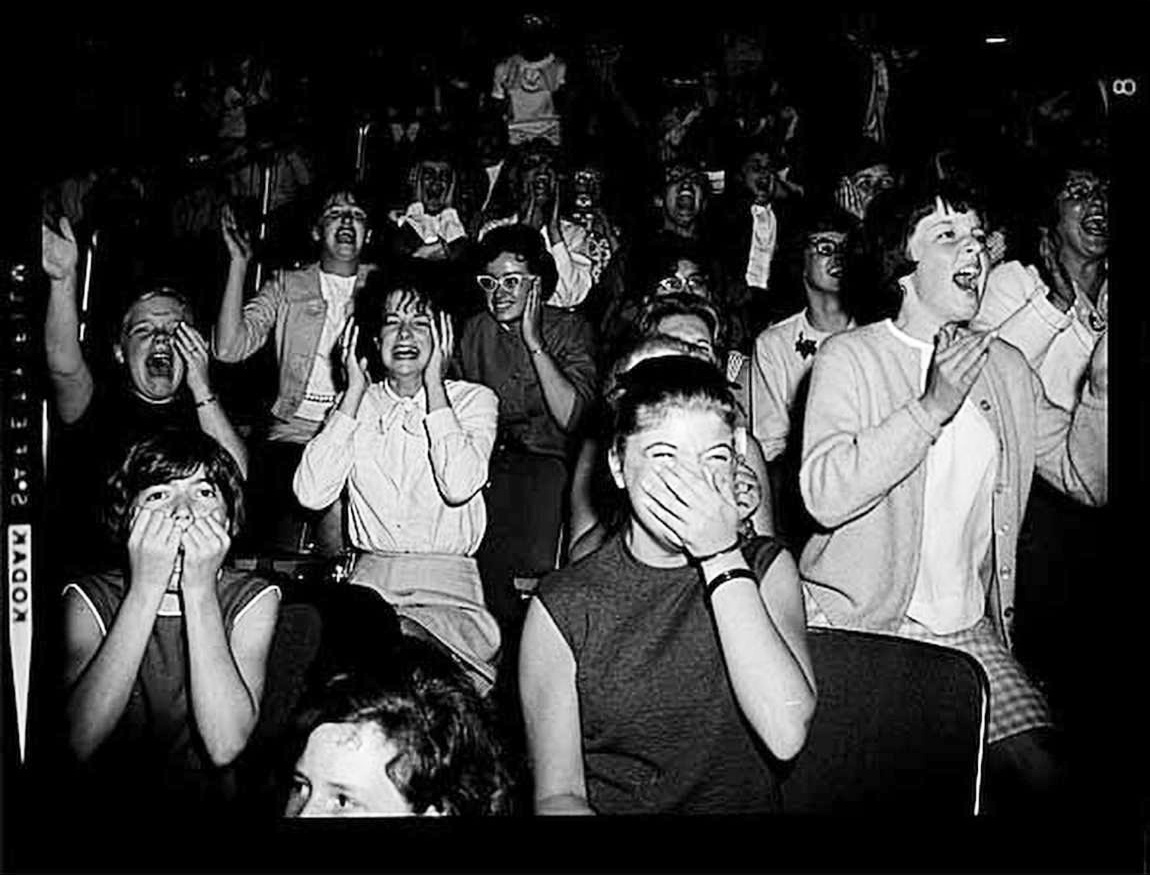

So that there could no doubt what Noebel meant by “African” music, he spelled out its allegedly vile effects. In the “heart of Africa,” wrote Noebel, “it was used to incite warriors to such a frenzy that by nightfall neighbors were cooked in carnage pots!” Such music, and its infusion into rock ‘n’ roll, Noebel charged, “is a designed reversion to savagery!” As ethnomusicologist Clara Henderson has shown, the Tarzan films of the 1930s had taught generations of Americans to associate not only violence with African “savagery” and jungle music, but a heightened sexuality as well.9 To illustrate the contemporary American counterpart to such alleged behavior, Noebel cited news reports of young people rioting and baring their skin during rock concerts. One eye-witness report of a 1964 Seattle, Washington, Beatles concert concluded simply, “It was an orgy for teenagers.” Speaking in Portland, Oregon about the Seattle concert, Noebel said, “Any girl so demoralized by music that she’ll tear off her clothes in front of 14,000 people will never be the same. The Communists are preparing our teen-agers for revolution.”10

Young fans cheer on the Beatles at the Seattle Coliseum in August 1964 (Courtesy Museum of History & Industry, Seattle, WA)

Young fans cheer on the Beatles at the Seattle Coliseum in August 1964 (Courtesy Museum of History & Industry, Seattle, WA)

Christian Recapitulationists

Decades after Noebel denounced the “savage” sound of the Beatles, fellow antievolutionists would attempt to pin responsibility for the scourge of racism on Charles Darwin and his evolutionary ideas.11 And yet, in the 1960s and 70s, Noebel and the Christian Crusade were engaging in the most naked racist appeals to convince American parents to protect their children from Satanically- and communist-inspired rock music. Ironically, in describing the supposed animalistic behavior of teenagers at rock concerts as a “reversion” to savagery, Noebel himself gave voice to a by-then scientifically discredited idea promoted by racist Lamarckian evolutionary enthusiasts in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth centuries. Making use of Ernst Haeckel’s concept of recapitulation, they had argued that human beings, in their individual development—their ontogeny—passed through the evolutionary history of their species—their phylogeny. According to this view, “primitive” behavior in otherwise “civilized” people was evidence of an “atavism,” an evolutionary throwback to an earlier stage of development.12 Such, as David Noebel told the tale, was apparently the fate of Seattle Beatle-loving teenagers. All it took to elicit that ancient trait was a bit of Communist-inspired jungle music.

Ideological Continuity

In considering Noebel’s work as part of the Red Dynamite tradition, it is worth comparing it to an earlier indictment of popular music that relied on both explicitly anticommunist and implicitly antievolutionary arguments: Henry Ford’s denunciation of jazz in the International Jew. On the authority of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Ford accepted the idea that Darwinism was a Jewish plot. And he openly identified the Jewish conspiracy as the source of the animalistic “grunts,” “squeaks,” “monkey talk,” and “jungle squeals” of 1920s jazz. In doing so, he went so far as to reject the idea that the music had fundamentally African roots.13 In a sense, Noebel did the opposite. In consonance with the new post–World War II style of fundamentalist anticommunism, it no longer was politically viable for Noebel to play the Jewish card. As Noebel reconstructs the communist cultural conspiratorial web, he says nothing explicitly about the role of Jews. But as one historian has observed, nearly all of Noebel’s readers would have noticed that “with few exceptions most of these subversives are Jews or blacks.”14 In this sense, there is a fundamental continuity between the conspiratorial anticommunist creationism of the 1920s and the 1960s.

Endnotes

-

David Noebel, Rhythm, Riots and Revolution (Tulsa, OK: Christian Crusade Publications, 1966), 90–91. For more on Noebel’s role in the conservative Christian backlash to rock music in the 1960s, see Randall J. Stephens, The Devil’s Music: How Christians Inspired, Condemned, and Embraced Rock ‘N’ Roll (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018), 102–45 and Mark Sullivan, “’More Popular Than Jesus’: The Beatles and the Religious Far Right,” Popular Music 6 (October 1987): 314–19. ↩

-

“Beware, the Red Beatles,” Newsweek, February 15, 1965, 89B; David Noebel, Suffer Little Children (Tulsa, OK: Christian Crusade Publications, 1967); Richard Reuss, “American Folksong and Left-Wing Politics: 1935–56,” Journal of the Folklore Institute 12 (1975): 89–111; Serge R. Denisoff, Great Day Coming: Folks Music and the American Left (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1971). ↩

-

David Noebel, Rhythm, Riots and Revolution, 250–329. ↩

-

Alexander Vucinich, Darwin in Russian Thought (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 233. ↩

-

David Noebel, Rhythm, Riots, and Revolution, cover; “Announcing America’s Most Needed Book of 1966,” Christian Crusade (1966), Billy James Hargis Papers, “Christian Crusade,” Box 4, Folder 53. ↩

-

On this aspect of Noebel’s writing on music, see John Haines, “The Emergence of Jesus Rock: On Taming the ‘African Beat,’” Black Music Research Journal 31 (Fall 2011): 232–35 and Berndt Ostendorf, “Rhythm, Riots and Revolution: Political Paranoia, Cultural Fundamentalism, and African-American Music,” in Ragnhild Fiebig-von Hase and Ursula Lehmkuhl, eds., Enemy Images in American History (Oxford, UK: Berghahn Books, 1997), 159–79. ↩

-

For Finkelstein’s perspective on American popular music, see Sidney W. Finkelstein, How Music Expresses Ideas (New York: International Publishers, 1952). On Finkelstein, see Maynard Solomon, Marxism and Art: Essays Classic and Contemporary (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1973; repr. 1979), 274–76. ↩

-

David Noebel, Rhythm, Riots and Revolution (Tulsa, OK: Christian Crusade Publications, 1966), 76, 86, 94; Howard Hanson, “Some Objective Studies of Rhythm in Music,” American Journal of Psychiatry 101 (November 1944): 364–69. ↩

-

Clara Henderson, “`When Hearts Beat like Native Drums:’ Music and the Sexual Dimensions of the Notions of “Savage” and “Civilized” in Tarzan and His Mate, 1934,” Africa Today 48 (Winter 2001): 91–124. Thanks to Professor Alisha Lola Jones for alerting me to this article. ↩

-

Ibid., 78–81, 110. “Speaker Sees Red Danger; Evangelist Cites ‘Moscow Records,” The Oregonian, Portland, Oregon, October 19, 1964, File 48, Box 3, Billy James Hargis Papers. ↩

-

See, for instance, Ken Ham, Darwin’s Plantation: Evolution’s Racist Roots (Green Forest, AR: Master Books, 2007). ↩

-

Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996; revised and expanded edition), 142–75. ↩

-

Jewish Influences in American Life, vol. 3 of The International Jew (Dearborn, MI: Dearborn Publishing, 1921), 65. ↩

-

Berndt Ostendorf, “Rhythm, Riots and Revolution: Political Paranoia, Cultural Fundamentalism, and African-American Music,” 171. ↩