Carl R. Weinberg

10 August 2022Balderdash?: A response to Richard Weikart’s review of Red Dynamite

by Carl R. Weinberg

In most cases, I don’t believe in responding to book reviews. You publish a book and let the chips fall as they may. In this case, however, I decided that a response was necessary. I hope you find it illuminating.

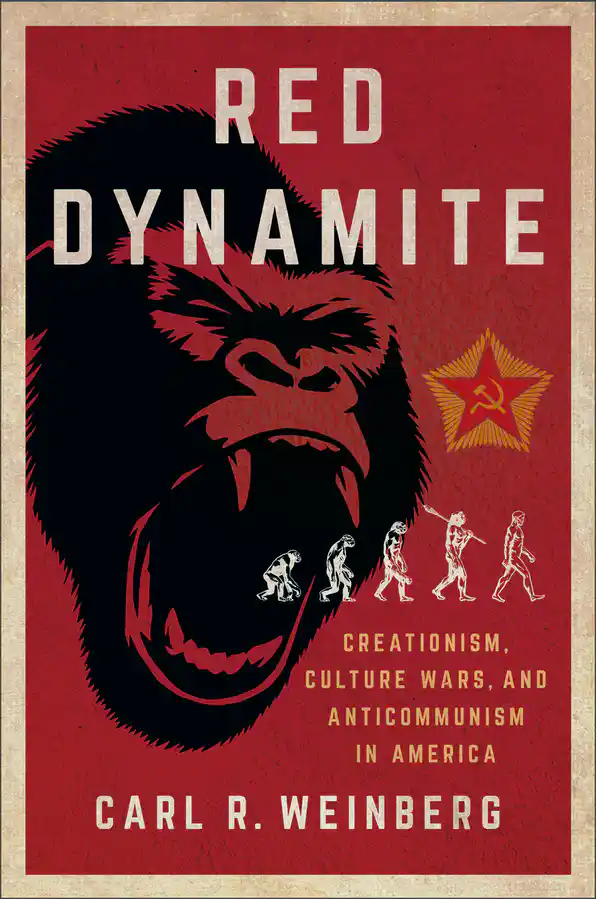

In early June 2022, historian Richard Weikart published a three-part review of Red Dynamite on the EvolutionNews website here, here and here. Maintained by the Discovery Institute, EvolutionNews promotes the theory of Intelligent Design (ID), a phenomenon I analyze in Ch. 8 of my book. Weikart is a Senior Fellow at the Institute’s Center for Science and Culture and, as an opponent of evolutionary science, has focused on demonstrating a link between Darwinism and Nazism. His best-known book is From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany (2004). While Weikart acknowledges that Red Dynamite takes a “meticulous” look at its subject, he also calls my arguments “bizarre,” “convoluted,” “slanderous,” and “balderdash.” He describes my Epilogue as “a virulent rant.”

Since I wrote the book to engage in a scholarly conversation about the history of creationism, I’m always glad to see a fellow scholar take the book seriously enough to review it, especially in three separate installments. At the same time, Weikart misrepresents my arguments in a number of ways that might mislead someone who has not read the book. Here I respond to a number of Weikart’s critiques in the interest of clarifying the issues under debate. I encourage everyone interested in these issues to read the book, which is available both as a free “open-access” download and a regular paperback, and come to their own conclusions.

The main point

In the first paragraph of his first post, Weikart summarizes the book’s purpose as “exposing creationism as a tool of Christian fundamentalists to attack communism (as well as other progressive moral causes, especially sexual immorality).” More accurately, the book is about anticommunism as a tool that Christian conservatives used to attack evolutionary science. It documents in great detail a rhetorical strategy pioneered by George McCready Price to link evolution to the alleged dangers and immoralities of communism, a connection Price labeled “Red Dynamite” in his 1925 book, The Predicament of Evolution.

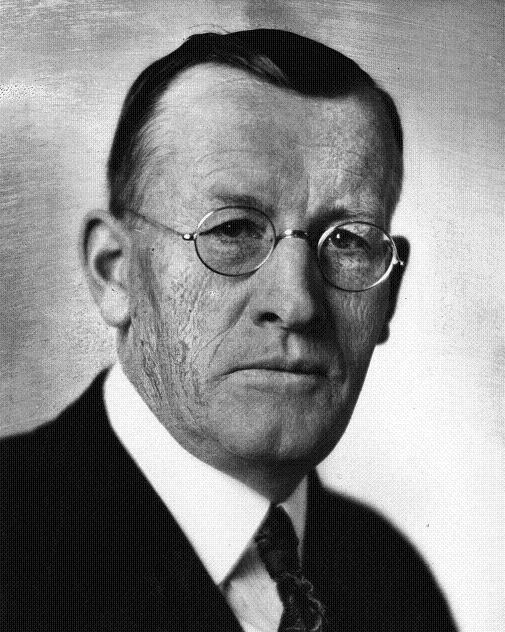

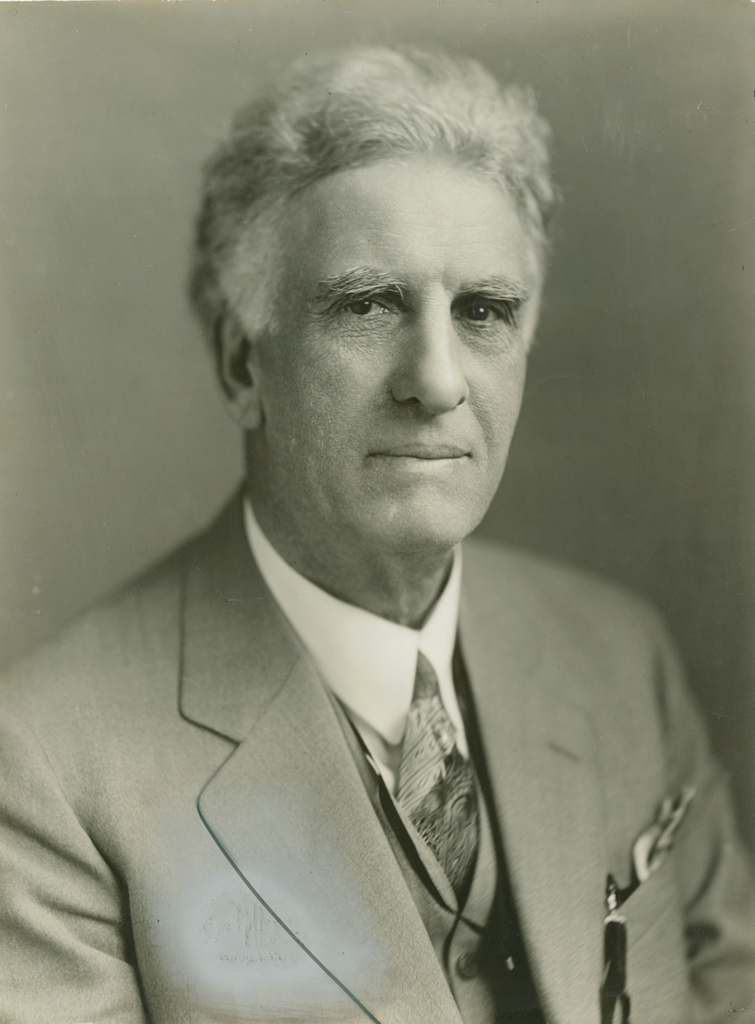

Creationist geologist George McCready Price (1870-1963) pioneered the “Red Dynamite” argument.

Creationist geologist George McCready Price (1870-1963) pioneered the “Red Dynamite” argument.

In the heart of my book, I demonstrate how succeeding generations of Christian conservatives and self-described “scientific” creationists continued this tradition. They included William Bell Riley, J. Frank Norris, Gerald Winrod, Aimee Semple McPherson, John R. Rice, and Henry Morris, among others. (Price’s name does not appear in Weikart’s review, continuing an unfortunate tradition of marginalizing this Seventh-day Adventist creationist pioneer.) Weikart’s first paragraph does have a plus side: he lays his own worldview on the table by describing sexual immorality as a “progressive moral cause.” In case you are wondering what kind of “immorality” progressives might consider moral, here’s a short list drawn from my book’s narrative: abortion, premarital sex, premarital dancing, masturbation, and same-sex marriage.

All about anticommunism?

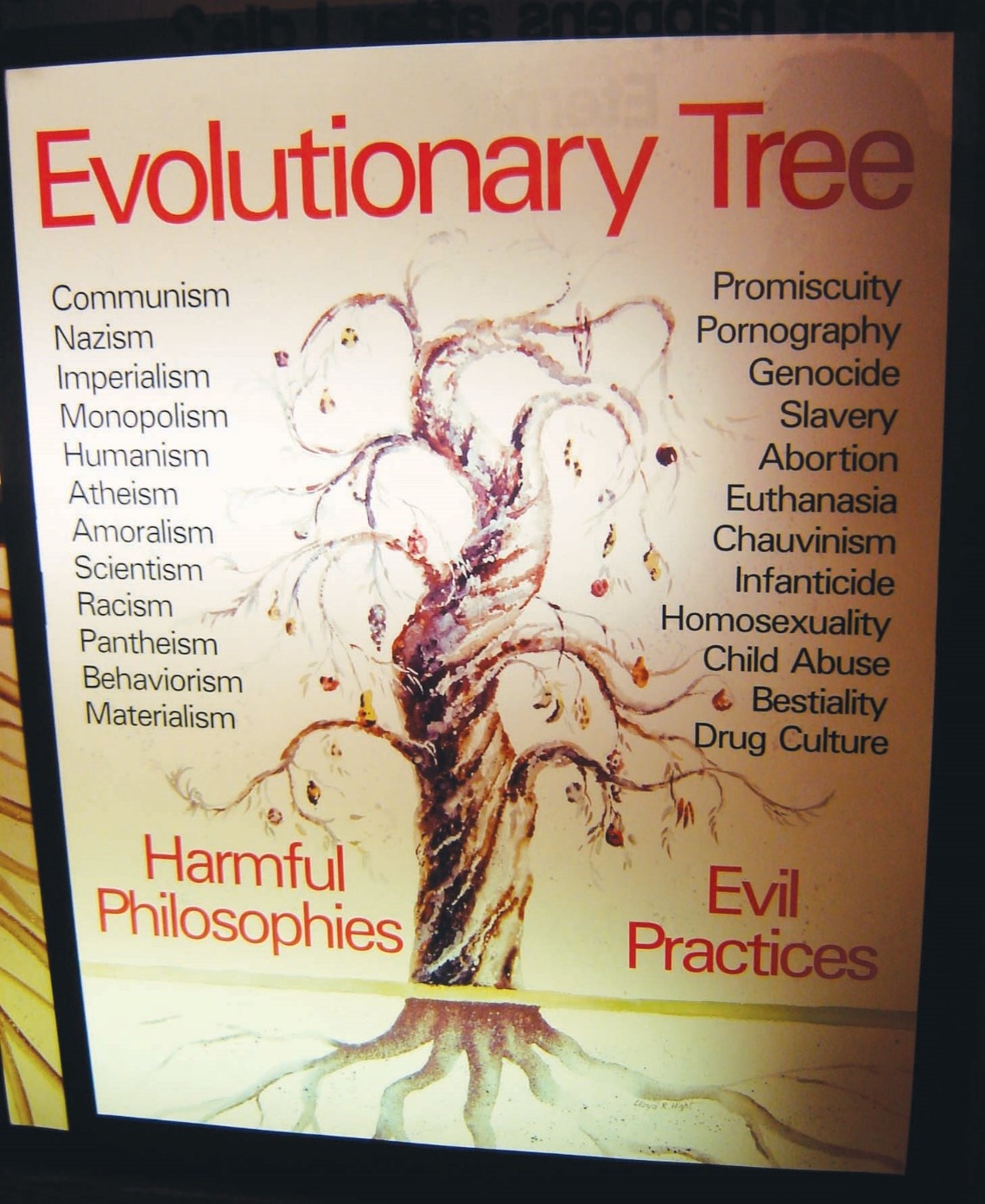

The rest of Weikart’s first post is devoted to assessing what he takes to be my major causal argument. As he indicates, I pose the following question in my introduction: “Why has creationism persisted into the twenty-first century in the most scientifically advanced country in the world?” According to Weikart, my answer is that creationists embraced creationism because of its association with anticommunism. “Balderdash,” says Weikart. Well, if that’s what I argued, he would be right. But my actual answer was different and broader: Christian conservatives “convinced their followers that evolutionary thought promotes immoral social, sexual, and political behavior, undermining existing God-given standards and hierarchies of power” (p. 13). Anticommunism was, I contend, not the whole deal, but “a key part” of this strategy. Socialism and communism, in this view, were “among the evil fruits” produced by evolutionary thinking. Evil fruits, I might add, that no historian before me has taken seriously.

Display in Institute for Creation Research museum in Santee, California, c. 2000. Communism tops the list of “evil fruits.”

Display in Institute for Creation Research museum in Santee, California, c. 2000. Communism tops the list of “evil fruits.”

The politics of religion

But even if Weikart were to accept my correction, we do have a real disagreement over how we interpret creationism. In my introduction, as Weikart notes, I assert that creationist opposition to evolution is not “primarily about science or religion, in a narrow sense, but about morality and power.” Weikart objects, saying that I’m ignoring creationist arguments that do rest on science and religion. For me, he says, “it must all be political.” Creationism, in my view, according to Weikart, “is just a bourgeois tool in the class struggle and serves as a justification for the oppressive capitalist system.”

Well, the book does show in many ways how creationism served to uphold existing relations of power, including between capitalists and workers. But I show that even Karl Marx did not dismiss religion as “just a bourgeois tool”. Moreover, I do not argue that religion has nothing to do with creationism. After all—and Weikart’s readers might be surprised to discover this—my second chapter features a deep dive into George McCready Price’s Seventh-day Adventist theology and how it provided a rich basis for his anti-evolutionary ideas.

The question really is, can religion and politics be disentangled? In my book’s introduction, I contend that “religion and politics . . . have always been inextricably intertwined.” That is, there is no religious realm that is completely disconnected from issues of power and morality. For me, that’s what politics is: who has power over whom and on what moral basis? For me, this inseparable connection between religion and politics explains why Answers in Genesis recently opened a major new exhibit on abortion at the anti-evolutionary Creation Museum. The exhibit’s name, Fearfully and Wonderfully Made, does come from scripture (Psalm 139: 14). But abortion is a deeply political matter. It is all about morality and power.

Indianapolis protesters denounce bill banning abortion in Indiana, July 2022.

Indianapolis protesters denounce bill banning abortion in Indiana, July 2022.

No solid ground for morality?

Speaking of morality, in his second post, Weikart claims that there is a contradiction between my defense of evolutionary science and my support for social evolution and the notion that morality can evolve. If we accept Darwinian evolution, says Weikart, then we have to accept as “natural” (that is, fixed and unchangeable) some pretty nasty behavior between humans: “oppressing the poor, waging warfare, and racial extermination.” But if we accept social evolution—as I do—then, asks Weikart, what basis can I have for presupposing that some things “such as oppressing the poor—are “objectively immoral”? It seems that I’m facing a terrible dilemma. Either there is the fixed amorality of the jungle, “Nature, red in tooth and claw,” or there is a fleeting, ever-changing morality that cannot provide a solid basis for my progressive politics.

Marxist morality

But Weikart has omitted a third alternative—Marxist class-based morality. In my discussion of President Ronald Reagan’s “evil empire” speech in Chapter 7, I give Reagan credit for accurately summing up Lenin and the Bolsheviks’ approach to morality. As Reagan put it, the Soviets “repudiate all morality that proceeds from supernatural ideas—that’s their name for religion—or ideas that are outside class conceptions. Morality is entirely subordinate to the interests of class war. And everything moral that is necessary for the annihilation of the old, exploiting social order and for uniting the proletariat.” (p. 235)

From this perspective, “oppressing the poor” is immoral because it’s part of the “old, exploiting social order,” not because it’s “objectively” wrong in some timeless, abstract sense. Incidentally, Reagan and his fellow anticommunists claimed that their morality was different. Reagan rejected the idea, at least in theory, that “whatever will further their cause” is moral, that the ends justify the means. But as I note in my Epilogue, Christian conservatives who supported the highly profane Donald Trump (more on this below) were operating on precisely that basis. For that matter, so was Reagan when he secretly and illegally funded the murderous contras in Nicaragua in order to destroy the 1979 Sandinista revolution.

Marxists and Lamarck

Weikart also faults me for downplaying the way that Marxists rejected Darwin in favor of Lamarck. I do address this point in Chapter 1 but not sufficiently for Weikart, which is understandable in that he wrote a whole book on the subject. It’s true that many nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century socialists liked Lamarck since he allowed acquired characteristics during an organism’s lifetime to influence future generations (think early giraffes stretching to get at higher leaves leading to longer necks which they passed on to their baby giraffes). In contrast, Darwin’s natural selection seems more passive and even sluggish. It depends not on behavior that changes the organism in its lifetime, but rather the existence of the raw material of natural variation in a population of organisms (some giraffes are born with slightly longer necks than others). Over a long period of time, if slightly longer necks helped those lucky giraffes to reach food and reproduce more successfully than shorter-necked giraffes, the average neck size in a giraffe population would grow.1 As I note, Lamarckism seemed more congenial for a vision of far-reaching social change where humans—interacting with the society around them— could rapidly transform their collective future.

How did giraffes evolve their long necks? Darwin and Lamarck gave different answers.

How did giraffes evolve their long necks? Darwin and Lamarck gave different answers.

Weikart not only says my treatment is inadequate but that on one key point, it’s just wrong. Weinberg, he says, “mentions Stalin’s embrace of Lamarckism, but wrongly portrays it as an aberration in an otherwise stellar communist performance in embracing what he calls ‘Marxist-Darwinism.’” First, I cannot take credit for that useful term—I borrowed “Marxist-Darwinism” from historian Nikolai Krementsov, a highly published specialist in Soviet history who provides an incisive analysis of early Soviet support for evolutionary science. 2

A non-Darwinist Lysenko?

Second, and more importantly, Weikart presents a false dichotomy between Darwinism and Lamarckism. The classic example of Stalinist Lamarckism gone wrong is the Soviet dictator’s support for agronomist Trofim Lysenko. Starting in the 1920s, Lysenko claimed that exposing winter wheat seeds to freezing temperatures before planting would allow them to be planted in the spring, leading to a big boost in crop yields. Just as the longer giraffe necks produced by stretching would be passed down to baby giraffes, the bigger crop yield would be inherited by the seeds of the resulting “vernalized” winter wheat plants. Over several decades, Lysenko’s Lamarckian methods, promoted by Stalin, led to the destruction of Soviet genetics and contributed to mass starvation. And yet, the prestige of Darwin’s discovery was still so strong in the 1940s that Lysenko’s supporters in the Stalinist bureaucracy referred to his efforts as “Soviet Creative Darwinism.” Strangely enough, and contrary to Weikart, in the Soviet context, one could be both a Lamarckian and a “Darwinist.” 3

Agronomist Trofim Lysenko (1898-1976) promoted “vernalization” of winter wheat using Lamarck’s concept of the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Agronomist Trofim Lysenko (1898-1976) promoted “vernalization” of winter wheat using Lamarck’s concept of the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Letting evolutionary biologists off the hook?

Weikart’s point about Stalin and Lysenko prefaces a broader critique of Red Dynamite in a section of Weikart’s second post entitled “Influenced by Non-Scientific Factors.” Here he restates the point that many Marxists who supported evolutionary science preferred Lamarck to Darwin not based on the science but rather on their political ideology. Weikart says this fact is “ironic” in light of my point that creationists were influenced by non-scientific factors (which indeed I do argue). Then comes Weikart’s retort: “Apparently, creationists are not the only ones influenced by non-scientific factors.”

If I had actually failed to recognize that evolutionary biologists were influenced by non-scientific factors, e.g., by their political views, that would be a serious omission. But here again, Weikart neglects to mention that in Ch. 7, I provide an extended case study of what I call “the influence of politics on biology.” (p. 213) In the 1970s, as I describe in detail, Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge challenged the prevalent model of evolutionary gradualism with their theory of punctuated equilibrium (PE). Led by Gould, the pair argued that ideas of the Darwinist mainstream were distorted and limited by a politically influenced commitment to imperceptibly slow change. In contrast, Gould and Eldredge argued for periods of slow change interrupted by quicker change (in an evolutionary timescale). After describing the content of PE and its ties to Gould’s own Marxist-influenced politics, I show how creationist Henry Morris correctly recognized the influence of non-scientific factors on Gould and Eldredge. (p. 216–17). (For that matter, I also review Morris’s largely accurate account of evolutionary science in the Soviet Union, including the outsize influence of Lamarckism.)

Stephen Jay Gould’s Marxist-influenced idea of puncuated equilibrium drew the attention of anticommunist creationists.

Stephen Jay Gould’s Marxist-influenced idea of puncuated equilibrium drew the attention of anticommunist creationists.

Have I slandered Henry Morris?

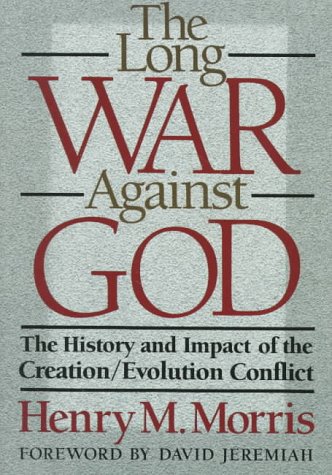

Weikart’s inattention to Gould and Eldredge might reasonably raise the question of whether or not he read Chapter 7. But we know that he did since he quotes from that chapter to accuse me of “making accusations” against Henry Morris “that are bizarre and even slanderous.” Here Weikart is referring to my discussion of Henry Morris’s 1989 book, The Long War Against God: The History and Impact of the Creation/Evolution Conflict. Weikart takes exception to my commentary on Morris’s chapter called “Political Evolutionism—Right and Left.” In Long War, Morris provides a wealth of examples from both sides of the political spectrum. As I note, this evidence “supported Morris’s contention that his opposition to evolution was not political, since both left- and right-wingers were, in practice, evolutionists.” I also observe the “seeming impartiality” of Morris’s treatment of Hitler and communists. Morris argues that Hitler was “the ultimate fruit of the evolutionary tree” and points out accurately that Marxists supported evolutionary science. But for all his attempts to place Hitler in the evolution camp, Morris was aware, as he admitted, of “certain attempts” to identify Hitler as a right-winger and even a Christian.” No, he wasn’t a Christian, says Morris, though he was an anticommunist.

Henry Morris’s 1989 magnum opus argued that evolution was the product of a centuries-long satanic conspiracy.

Henry Morris’s 1989 magnum opus argued that evolution was the product of a centuries-long satanic conspiracy.

At this point in my text, I write the following, quoted in full by Weikart: “Morris offers no additional information to his readers about Hitler’s anticommunism—an essential ingredient in Nazi ideology. In effect, Morris admits that Hitler was ‘one of us’ in his militant anti-communism but fails to explore that common ground that had led William Bell Riley—who had chosen Morris as heir apparent at Northwestern—to praise Hitler and led others to sympathize more quietly with him.” Weikart objects to my statement that Morris considered Hitler “one of us,” since Morris’s description of Hitler as “evil fruit” shows that he opposed Hitler. And Weikart says that I have unfairly linked Morris to Riley through “guilt by association,” implying falsely that Morris supported Hitler. I therefore owe Morris a “posthumous apology.” (He died in 2006.)

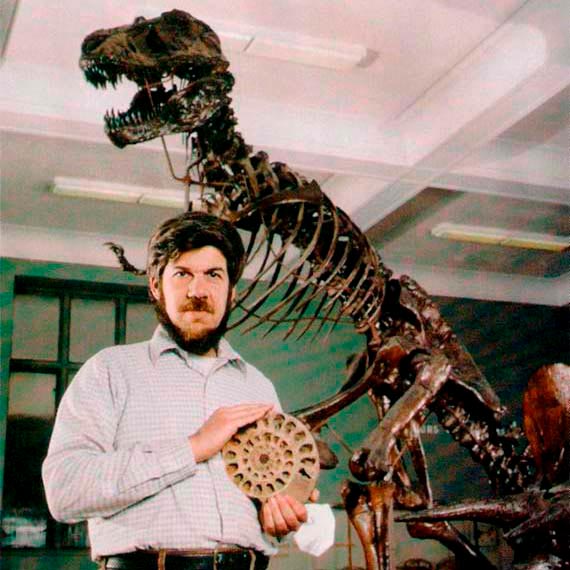

Henry Morris (1918-2006) founded and led the Institute for Creation Research

Henry Morris (1918-2006) founded and led the Institute for Creation Research

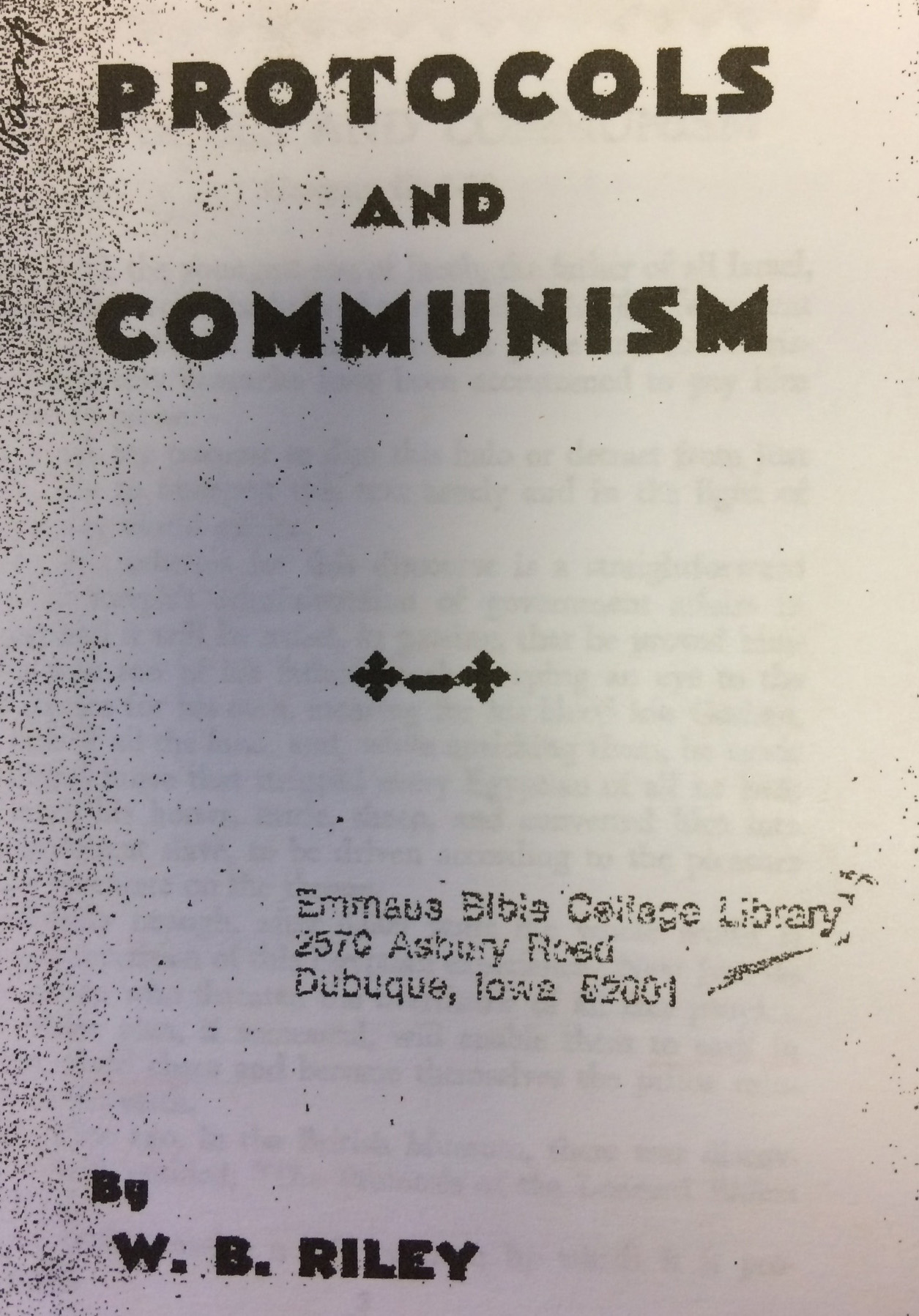

Morris and Riley’s tainted legacy

Let’s first deal with the relationship between Morris and William Bell Riley. In 1946, as I detail in Chapter 6, Morris published his first book, That You Might Believe, in which he attributed a wide variety of social, moral, and political evils to the “atheistic and satanic character” of evolutionary science. After reading the book, William Bell Riley called Henry Morris and offered him a job as his successor at Northwestern Bible College in Minneapolis. In the previous decade, Riley had tied evolution to an international Jewish communist conspiracy, based on the fabricated Protocols of the Elders of Zion, and publicly hailed Hitler for standing up to this alleged conspiracy in Germany. (Though Riley did a rapid about-face when the US entered the war and then blamed evolution for Hitler, he said not a single word about Hitler’s Jewish victims.)

William Bell Riley’s book attributed evolution to a Jewish-Communist conspiracy.

William Bell Riley’s book attributed evolution to a Jewish-Communist conspiracy.

Though nowhere in my book do I say that Morris shared Riley’s views on Hitler and Jews, I stand by the following: “Riley was correct to see in Morris’s writings a continuation of what the older man had started. Not only did these two men share a fundamentalist Baptist faith, but they agreed that evolution posed great dangers for American society, morality, and politics.” Though Morris declined Riley’s offer—for one thing, Morris was then a graduate student at the University of Minnesota planning a secular academic career—he maintained links with Riley’s bible college for decades after the old man’s death.

William Bell Riley (1861-1947) was a leading Christian fundamentalist and opponent of evolutionary science.

William Bell Riley (1861-1947) was a leading Christian fundamentalist and opponent of evolutionary science.

How did Morris think about Hitler? It was 1989. The political environment had changed drastically since the 1930s, when Henry Ford, William Bell Riley, and Gerald Winrod had all publicly lauded the Nazi party. It had become rare for anyone, even on the political right, to openly express admiration for Hitler. What we do know, and what I document in the book, is how Morris compared the Nazis and the communists in Long War Against God. What I find is that Morris links communists, evolutionists, and Satan (but not Hitler) in a centuries-long conspiracy that has killed more people in the twentieth century (in the “class struggle”) by a factor of “ten or more” than the number of Hitler’s victims.

So, let us return to the “offending” sentence: “In effect, Morris admits that Hitler was ‘one of us’ in his militant anti-communism but fails to explore the damaging implications.” That is, Morris says essentially, yes, Hitler was a right-winger in that he was a militant anticommunist. I don’t write that Morris literally said that Hitler was “one of us.” I wrote, “in effect,” which is to say, Morris acknowledged that he did share some political common ground with Hitler. What were the implications of this common ground that Morris failed to explore? One of them was that for William Bell Riley, the “grand old man of midwestern fundamentalism,” the man who launched the World’s Christian Fundamentals Association, and who offered Morris a job as his successor, anticommunism had led to public political sympathy for Hitler’s Nazi Party. That is, the movement Morris was now leading had a historical tie to open support for Hitler based on a shared Jew-hating, conspiracy-mongering anticommunism. Saying this is neither bizarre, nor slanderous. It’s simply, if uncomfortably, true.

Intelligent Design and the Discovery Institute

In Weikart’s third and last post, he addresses a subject that cuts closest to home for him—Intelligent Design (ID) and the organization he is affiliated with, the Discovery Institute. Weikart argues that my discussion of the Discovery Institute is flawed in a number of ways and concludes: “Thus, Weinberg’s argument here is extremely weak: he never shows that ID proponents at Discovery Institute link intelligent design with anti-communism.”

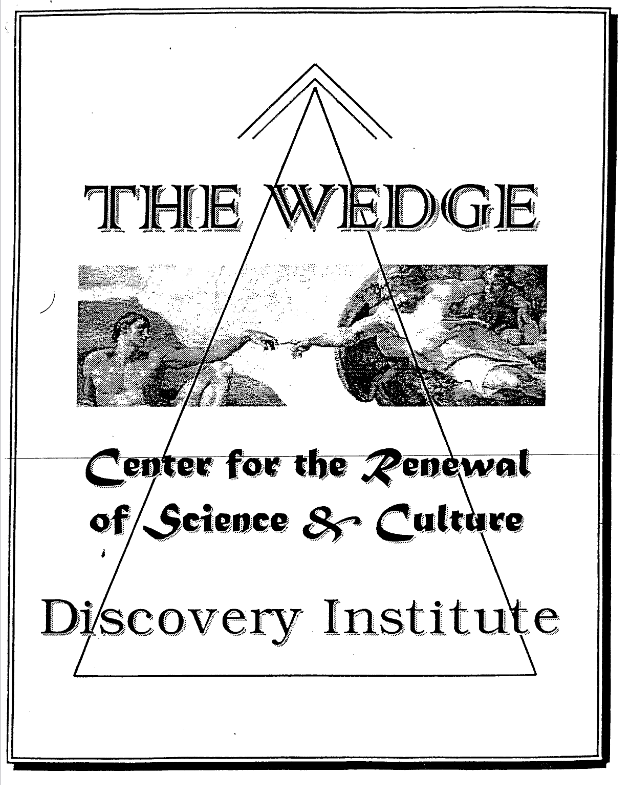

The Wedge Document

And yet, Weikart neglects my entire discussion (pp. 259–61) of the infamous “Wedge document”. This was an initially private, internal, five-year fundraising plan for the Center for the Renewal of Science and Culture (CRSC) that was leaked online in 1999. The content of the document made it clear that the Discovery Institute operated from a particular worldview that aimed, in their words, to “defeat scientific materialism and its destructive moral, cultural, and political legacies.” That is, the leaders of the Discovery Institute were looking to demonstrate more than the truth of intelligent design: they sought to reverse social changes they thought were harmful. Among these were the projects of “materialist reformers” who “promised to create heaven on earth”—that is, socialists and communists. By the way, the document identified the chief advocates of the “materialist conception of reality” as Darwin, Marx, and Freud. The fallout from this episode led the Institute to rename the Center for the Renewal of Science and Culture as the Center for Science and Culture (with which Weikart is currently affiliated). Removing Renewal downplayed any sense that the Institute was practicing politics. So, while it may be true that I could have spent more time fleshing out the details of ID, the Wedge Document is positive evidence that, in Weikart’s words, “ID proponents at Discovery Institute link intelligent design with anti-communism.”

The Wedge document, revealed online in 1999, provides insight into the politics of Intelligent Design.

The Wedge document, revealed online in 1999, provides insight into the politics of Intelligent Design.

A virulent rant?

Last but not least, I will address Weikart’s claim that the Epilogue of Red Dynamite is a “virulent rant against Trump and his supporters.” Especially because Weikart couches this comment with an acknowledgement that “For the most part the book is not a diatribe,” his claim about my Epilogue may sound credible to his readers. When I initially read Weikart’s review, I decided that due diligence required me to reread my Epilogue and look for evidence of a virulent rant. I first consulted the Oxford English Dictionary for some definitions. Virulent means “violently bitter, spiteful, or malignant.” A rant is “an extravagant, bombastic, or declamatory speech or utterance.” If I had written such a rant, Weikart could have easily demonstrated my virulence to his readers with some well-chosen quotations. But he does not offer a single example. As it turns out, that’s because there are no such quotations to be found in my Epilogue.

The actual Epilogue

Upon reviewing the text of my Epilogue, here’s what I did find: I discuss the 2016 election campaign and conservative evangelical support for Trump. I bring attention to the seeming oddity of anti-evolutionists supporting “’social Darwinism’ incarnate.” I document how Ken Ham of Answers in Genesis spoke favorably about Trump. Here’s a representative sample of how I write about Trump and his prominent evangelical supporters such as Rev. Robert Jeffress: “Like Ken Ham, they recognized that millions of rank-and-file evangelicals were drawn to Trump’s plainspoken calls for barring immigration from Mexico and the Middle East, his denunciation of trade deals, his ‘outsider’ status, his nostalgia for a mythical American past, and his willingness to tell the truth about the miserable economic conditions facing working people” (pp. 272–73).

Donald Trump speaks at Liberty University during 2016 presidential campaign.

Donald Trump speaks at Liberty University during 2016 presidential campaign.

As for those working-class Trump supporters, I do write about one group of them in the Epilogue—the coal miners from Harlan County, Kentucky who blocked train tracks and prevented their employer, Blackjewel LLC, from shipping coal in protest of non-payment of wages. As I note, Harlan County went 85 percent for Trump, and these workers probably voted for him. In any event, they are among my heroes. In sum, I have failed to find any ranting, virulent or otherwise.

Coal miners block railroad tracks in Harlan County, Kentucky to protest non-payment of wages by their employer Blackjewel LLC, July 2019.

Coal miners block railroad tracks in Harlan County, Kentucky to protest non-payment of wages by their employer Blackjewel LLC, July 2019.

In conclusion

All in all, I thank Richard Weikart for giving me the opportunity to clarify these matters. I thank him as well for using the ancient, charming word “balderdash.” I look forward to sharing that word, his review, and this response with my students.

Endnotes

-

For purposes of this response, I have simplified a complex story. In reality, even though Darwin emphasized natural selection as the main mechanism of evolution, he made some room in On the Origin of Species for “use inheritance,” that is, Lamarck’s idea, widely accepted, that the use and disuse of bodily organs would change what organisms passed onto their offspring. ↩

-

Nikolai Krementsov, “Darwinism, Marxism, and genetics in the Soviet Union,” in Denis R. Alexander and Ronald L. Numbers, eds., Biology and Ideology: From Descartes to Dawkins (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 215–46. ↩

-

Alexei V. Kouprianov, “The Soviet Creative Darwinism (1930s–1950s): from the Selective Reading of Darwin’s Works to the Transmutation of Species,” Studies in the History of Biology 3 (June 2011): 8–31. ↩